Cosmin Minea

A small but lavishly decorated eighteenth-century monastery in the centre of Bucharest reveals different ideas about the conservation and promotion of historical monuments in early twentieth-century Europe and gives important lessons about the management of heritage sites today.

For the increasing number of tourists who visit Bucharest every year, Stavropoleos is a familiar name. The small monastery is situated right in the heart of Bucharest’s tourist hotspot, known as ‘the old centre’, and constitutes an unusual site among the pedestrian streets lined with outdoor terraces, night clubs and shops.

Credits: www.editiadedimineata.ro

Its fame as a top cultural attraction of Bucharest is not, however, due to mass tourism. Ever since the creation of Romania in 1859 (from the union of two principalities, Wallachia and Moldavia) Stavropoleos Monastery and specifically its church have been promoted as a symbol of Romania’s cultural heritage. In the early twentieth century it inspired architects to create modern buildings that reinterpreted the architectural forms of the church in a new style that became known as the Neo-Romanian Style. This post will focus on the less-known, albeit controversial, restoration of Stavropoleos (1897–1908) and explain different theories about architectural heritage management. It will examine the lessons this offers for the way we see and manage historical monuments and heritage sites today.

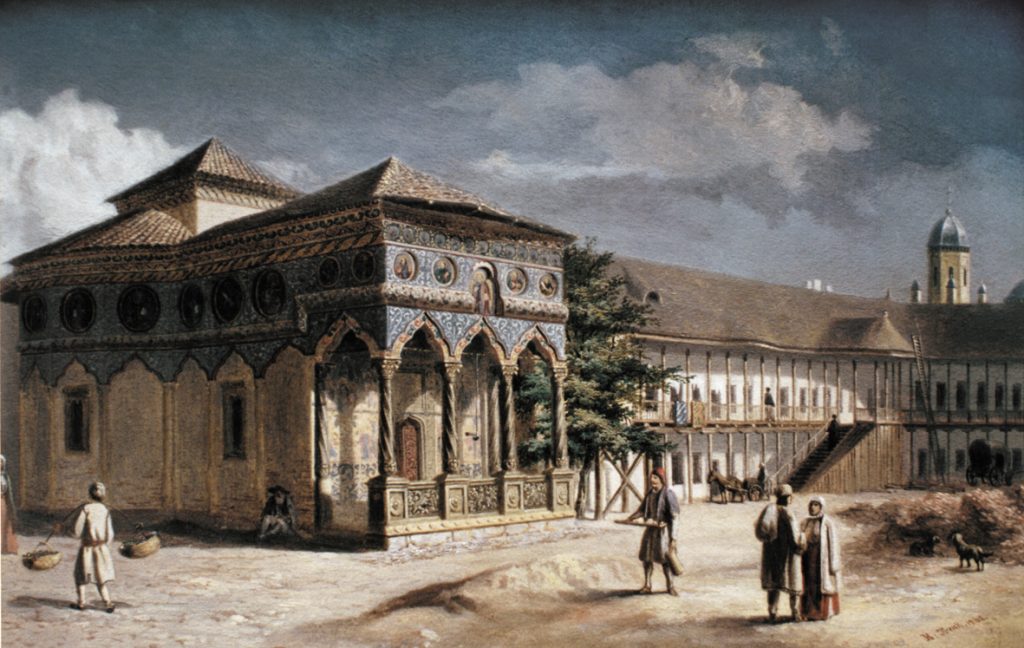

The small Stavropoleos Monastery was built in 1724, during the so-called Age of the Phanariots (1714–1821), when Wallachia was ruled by ethnic Greek princes from Istanbul. In fact, the founder of the monastery was also Greek (a monk called Ioanichie), as was the name ‘Stavropoleos’. The complex comprised a church surrounded by single-storey buildings with exterior galleries which housed the monastic community, merchants and visitors.

In the nineteenth century, a time when Romania was focusing its energies on westernising the architectural styles of its Capital, Stavropoleos was ignored and fell into disrepair. From a prosperous monastery, it became simply a small church, without its former cloister, surrounded by tall, modern buildings and badly in need of renovation.

After the formation of Romania in 1859, the church started to be noticed by artists and historians interested in the country’s national past (for example, it inspired the portico of the Romanian pavilion at the 1867 Paris World Fair). A decisive moment for the modern history of Stavropoleos came in 1897 when the Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Instruction asked the architect Ion Mincu (1852-1912) to design a restoration plan for the church. Mincu was not just any architect, but the main authority on old Romanian monuments and a pioneer in using historical architecture in modern designs. Somewhat surprisingly, he was not very enthusiastic about Stavropoleos. He saw the church as built of cheap materials, with extremely weakened walls, on a ‘small and obscure parcel of land’ with ‘abhorrent surroundings’.i His proposal was a radical one: demolish the church and faithfully reconstruct it in another site, where it would be surrounded by a brand new museum of Romanian architectural heritage, comprising large galleries in the same architectural style as Stavropoleos, that would host artefacts gathered from across the country.

Ion Mincu is remembered in Romania as a great patriot and defender of the nation’s architectural monuments. But his vision for Stavropoleos did not include what most would expect: the preservation and protection of the building as an intact ‘witness’ of the past, worthy of being displayed untouched, like a museum exhibit. Mincu’s proposal to demolish and reconstruct the monument within a new museum demonstrated his interest in creating new works of art, reimagining buildings and modifying and placing the historical heritage in a new, contemporary context. He saw historical monuments primarily as opportunities for developing a modern language of art and architecture in Romania. This is why he imagined a complete restoration and relocation of the church, together with the design of a new museum whose architecture would be inspired by Stavropoleos. His proposal was indeed an attempt to revive the country’s architectural heritage through modern creations and stimulate the production of new architecture in Romania. Mincu would directly confirm his interest in contemporary architecture four years later, in 1901, when he was asked for a further restoration proposal for the monastery. This time he referenced directly the needs of architects, arguing that ‘The consolidation [of the existing church] would not prevent the disappearance over time of many artistic elements. Therefore, a perfect copy of the church should be built in another place in order for the next generations of artists to possess a preserved, detailed example of our domestic art.’ii

The Commission for Historical Monuments rejected Mincu’s restoration plan, bluntly stating that ‘Respect for the past does not allow the destruction of a building, no matter its current state.’iii The Romanian authorities’ reluctance to accept a daring plan of heritage revival owed much to a prominent public scandal some ten years before, involving the restoration of monuments. Many of those who later became members of the Commission and Ministry had strongly criticised a royal-appointed French architect, André Lecomte du Noüy, for demolishing and modifying some of the country’s most important churches and monasteries. It was essentially a debate between the passive preservation and active reconstruction of architectural monuments, with (regrettable) nationalist undertones since the restorer was resented for being a foreigner. Paradoxically, Mincu’s proposal recalled the approach of the French architect.

Mincu’s proposal was not only rejected by the authorities, but also opposed in a much more public way. His intentions were directly challenged by one of the most ardent promoters of Romanian material heritage, Alexandru Țigara-Samurcaș (1872-1952). The first Romanian art historian with a doctorate (awarded in Munich, 1896), Samurcaș well understood that Byzantine religious art was admired in Europe through the grand examples of important churches in Istanbul, Venice or Ravenna. He did not consider that a small church, looking nothing like the big Byzantine cathedrals, was in any way prestigious. He criticised it for being in ‘a heterogeneous style’ that was not representative of ‘the true Byzantine style’; it had a small, simple architectural plan like ‘a country church’ and was built with cheap construction materials (plaster and brick).iv Samurcaș was, moreover, interested in monuments that could be related to prestigious rulers or historical events. In his view, Stavropoleos had little historical significance since it was a relatively recent construction from 1724, and its founder was ‘an obscure Greek monk’. He proposed only to consolidate the church to prevent its collapse, arguing that to reconstruct it ‘means to give to Romanian architecture a proof of misery that it surely does not deserve’.v Indeed, maybe Samurcaș was right. How could a small, atypical monument, with no age value, founded by a ‘foreigner’, pass as a national symbol?

Mincu’s response was a passionate defence of the idea of innovative architecture that does not conform to established styles but is representative of a particular place and culture. His statement identifying a ‘Romanian’ architectural style at Stavropoleos has come to be considered the first ever definition of national Romanian art:

Precisely because it is not made in ‘pure Byzantine style’, the church represents for us a very precious ‘archetype’. From the pure Byzantine style, it evolved into the heterogenous style, to use Mr. Samurcaș’s term, and this I call ‘Romanian style’. Stavropoleos Church is therefore the last form of the development of local art and the end road from where we have to restart the tradition. The monument is a guiding and inspirational source for our future generations of artists.vi

Mincu argued that we should not only value famous examples and fixed architectural canons, but that original and atypical architecture has great value for a nation precisely because it is not similar to other monuments. In contrast to Samurcaș, he placed the value of a monument in its visual aspect, decorations and architectural forms, and not in the date of its construction, the importance of its founder, or its general layout and size.

Mincu eventually reached a compromise with the Commission on the restoration of Stavropoleos. He did not demolish or relocate the monument, but organised its extensive restoration. Over four years (1904-1908), the exterior decoration of the church was repainted, twenty-four capitals were renewed and the middle frieze, barely visible at the time, was replaced with a new stone one. A new tower was built in a different form, the roof was replaced and the interior furnishings restored. Throughout, Mincu did not aim for historical accuracy, but tried to highlight the aesthetic and artistic quality of the built heritage.

But the most visible result of the restoration was the building, in 1908–12, of a museum surrounding the church, as Mincu had initially envisaged. Here Mincu created a unique, eclectic construction that referenced architectural and decorative elements from the church, but on a monumental scale, in a two-storey high building that also included a bell tower. The inner courtyard, with its arcade of trefoil arches modelled on the church’s porch, resembles the cloisters of Catholic monasteries from Italy or Spain. The building is relevant for the multiple artistic sources used and for the experiments with various architectural motifs that marked the latter part of Mincu’s career. Elements from Romanian heritage were combined with great freedom and mixed with other sources.

Credits: Luca Volpi (Goldmund100)

Mincu did not see architectural heritage as something sacred or frozen in time, but rather as something to be reshaped, modified and made usable in contemporary society. Even if, since 1991, the former monastery has been restored and Mincu’s museum reconverted into a convent cloister, lessons can be drawn from his intentions. As the case of the current restoration of the spire of Notre Dame Cathedral shows, debates about how to preserve or restore monuments are very much alive today. Mincu, more than one hundred years ago, offered an interesting answer to a question that is still heatedly debated today: to what extent should the needs or values of contemporary society prevail over principles of protection and the strict preservation of historical artefacts?

Further reading:

- Ada Hajdu, ‘The Search for National Architectural Styles in Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria from the Mid-Nineteenth Century to World War I’, in Entangled Histories of the Balkans. Volume Four: Concepts, Approaches, and (Self-)Representations, ed. by Roumen Daskalov et al. (Leiden: Brill, 2017), iv, 394–439;

- Shona Kallestrup, Art and Design in Romania 1866-1927: Local and International Aspects of the Search for National Expression, Eastern European Monographs (Boulder, Co.: Columbia University Press, 2006);

- Cosmin Minea, ‘The Monastery of Curtea de Argeș and Romanian Architectural Heritage in the Late 19th Century’, Studies in History and Theory of Architecture, 4 (2016), pp. 181–201

- Gh. Nedioglu, ‘Stavropoleos’, Buletinul Comisiunii Monumentelor Istorice, 17, October-December (1924), pp. 147-168

- Carmen Popescu, Le style national roumain: construire une nation à travers l’architecture, 1881-1945 (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2004);

Endnotes

i Report of January 5, 1900 in the Archive of the Ministry of Religious Denominations reproduced in Gh. Nedioglu, ‘Stavropoleos’, Buletinul Comisiunii Monumentelor Istorice, 17, October-December (1924), pp. 147-168, p. 163. Also, Nicolae Petrașcu, ‘Ioan Mincu’, (Bucharest: Cultura Națională, 1928), p. 90.

ii Gh. Nedioglu, ‘Stavropoleos’, Buletinul Comisiunii Monumentelor Istorice, 17, October-December (1924), pp. 147-168, p. 164.

iii Nedioglu, ‘Stavropoleos’, p. 63.

iv Alexandru Țigara-Samurcaș, Scrieri Despre Arta Românească (Bucharest: Meridiane, 1987), pp. 260–61.

v Samurcaș, Scrieri,pp. 262–63.

vi Ion Mincu, ‘Cronică Artistică – Stavropoleos (Răspuns d-Lui Tzigara-Samurcaş)’, Epoca, 25 March, no. 83 (1904)’, pp. 282–84.

Art Historiographies in Central and Eastern Europe

Art Historiographies in Central and Eastern Europe