A signed copy of George Oprescu’s 1935 book Roumanian Art from 1800 to our Days in St Andrews University Library reveals fascinating links between Scottish and Romanian academics in the interwar period.

Shona Kallestrup

______

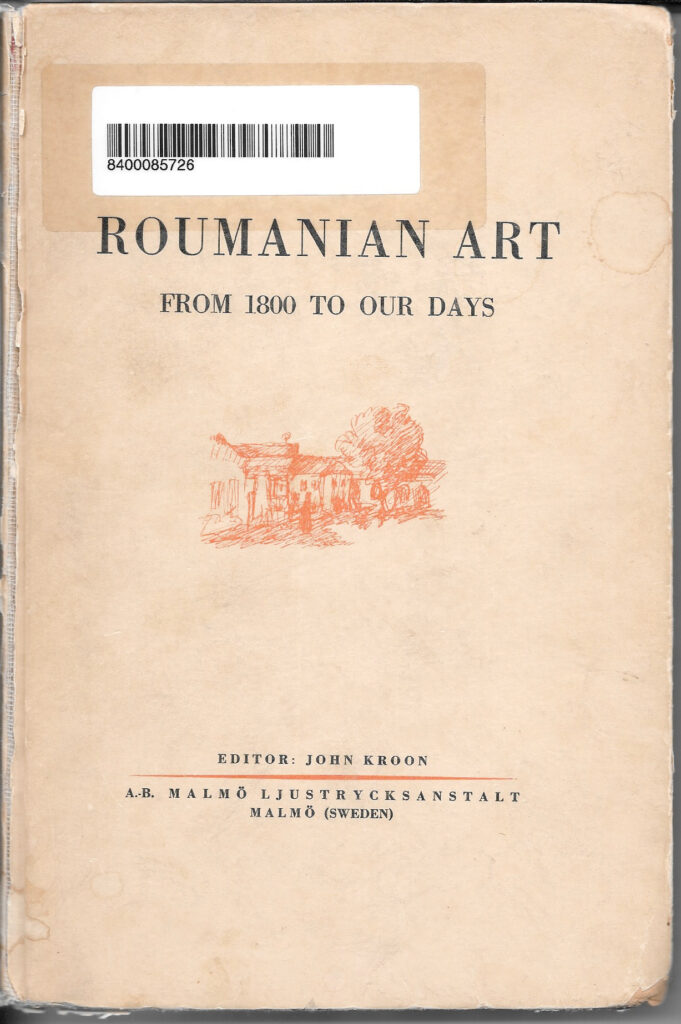

Among the few books on Romanian art in the library of St Andrews University is a signed copy of George Oprescu’s Roumanian Art from 1800 to Our Days, published in 1935 in Malmö. Oprescu (1881-1969) was one of Romania’s most important art historians; he held the Chair of Art History at the University of Bucharest and founded the Institute of Art History (part of the Romanian Academy) which today bears his name. This English translation of his book, together with the original French version, was commissioned by the Swedish editor John Kroon who had met Oprescu at the 1933 International Congress of Art History in Stockholm and persuaded him ‘to give a conspectus of the artistic movement in Roumania in the XIXth and XXth Centuries’.[1] It represented the third attempt (and the first in English) to present modern Romanian art to an international public,[2] and comprises a short, fifty-page, summary essay, followed by an extensive photo catalogue divided into painting, sculpture and architecture. Important both for the rich number of images made available to a western audience for the first time, and for the significant presence of women artists (nine painters, five sculptors and one architect), Oprescu’s short volume was one of the very few internationally-accessible publications on modern Romanian art before the ideological rupture of communism distorted art historical scholarship on the pre-socialist period.

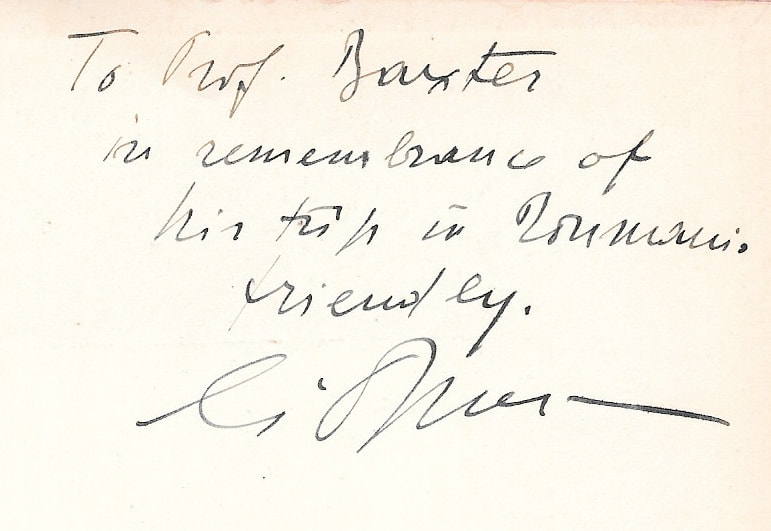

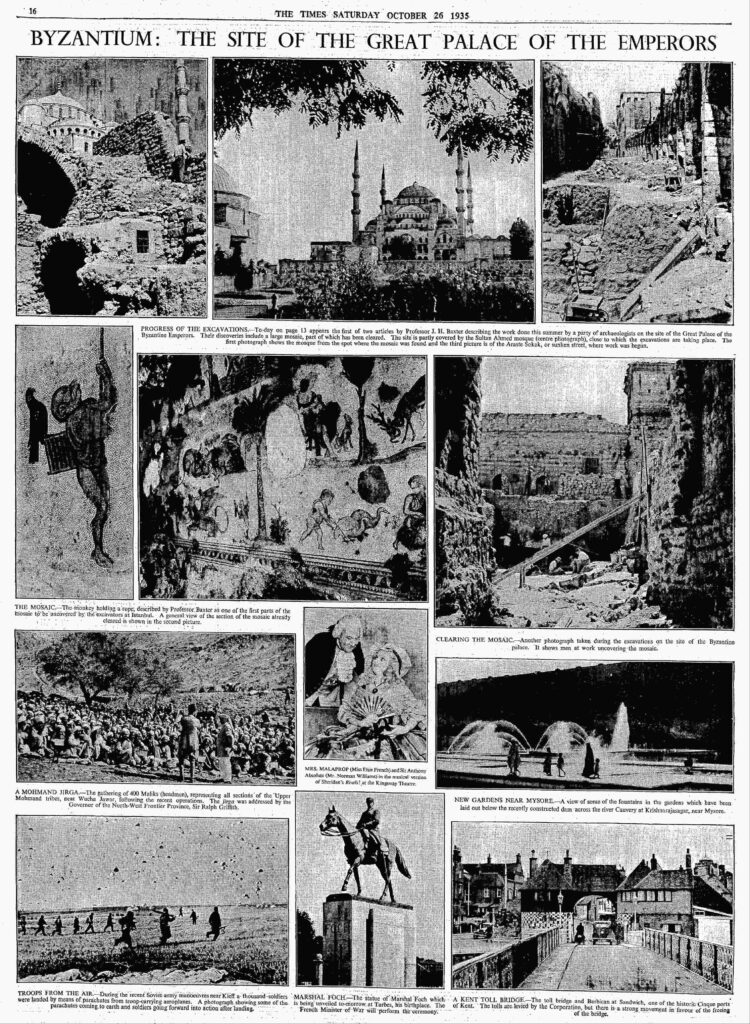

The St Andrews volume carries an inscription on the first page: ‘To Prof. Baxter in remembrance of his trip in Roumania. Friendly, G. Oprescu’, together with a presentational label to the library from ‘Professor J. H. Baxter, DLitt, etc, 1939’. James Houston Baxter (1894-1973) held the Chair of Ecclesiastical History at St Andrews from 1922-70. He is most famously remembered for the series of excavations of the Great Palace of the Byzantine Emperors in Constantinople that he conducted for the Walker Trust between 1933-39. Recent research by Dr Lenia Kouneni of the School of Art History at St Andrews has revealed the curious story of the spiritualist underpinnings of this venture, which originated as a paranormal quest to find the remains of Justinian’s Library. Funded by the Markinch paper-mill owner David Russell, via the Walker Trust that his great uncle had set up to support the University, the excavations were the result of Russell’s friendship with the neo-Christian mystic Major Wellesley Tudor Pole, who had ‘discovered’ the purported location of Justinian’s Library through spiritualist séances with Russian exiles in Paris. Professor Baxter, with the weight of St Andrews University behind him, was subsequently engaged to give a legitimate academic front to the enterprise. Luckily for Russell and Baxter, the excavations – although finding no evidence of the Library – very quickly came upon an extensive, mosaic-paved peristyle hall, today considered one of the finest material discoveries of imperial Byzantium.[3]

It was in the course of Baxter’s journeys to and from Istanbul that he regularly passed through Romania en route to cross the Black Sea from the port of Constanța. He made contact with several of the most important Romanian intellectual figures of the day: together with Oprescu these included the leading historian, eminent Byzantinist and (from 1931-32) Romanian Prime Minister, Nicolae Iorga; as well as the famous writer Princess Martha Bibescu. Barely a decade, then, before the descent of the Iron Curtain severed Romania’s complex cultural and political links with Western Europe, Baxter found himself part of a rich transnational network of intellectual exchange that stretched from the Balkans to Scandinavia, evidence of which is preserved today in his correspondence in the St Andrews archives and in the books he donated to the library. Taking Oprescu’s art historical gift as a starting point, this blog will briefly explore some key points that emerge from the entangled history of the Romanian scholar and the St Andrews Byzantinist.

First, let us place Oprescu’s book in its art historiographical context. Art History only really emerged as a self-confident discipline in Romania in the 1920s with the work of scholars like Oprescu, Iorga, Alexandru Țzigara-Samurcaș and Coriolan Petranu. This, in turn, was a result of the widescale adoption of western academic frameworks that accompanied Romania’s emergence as an independent state and rapid re-orientation from Oriental to Occidental models in the nineteenth century. This abrupt volte-face had brought with it the introduction of western easel painting, sculptural traditions and beaux-arts architecture, together with the academies and salons that supported them. Yet the country’s longer historical artistic evolution, characterised by a strong Byzantine and folk tradition, did not fit comfortably into the art historical models developed in Western and Central Europe. Romanian art historians struggled with the problem of how to bridge the cultural caesura of the nineteenth century and link the religious art of the past with the very different forms of modern secular painting, sculpture and architecture. Oprescu explained that his book was an attempt, therefore,

to throw into relief the circumstances, outward or subjective, which surround and explain the development of the Roumanian school […] in a word all the various features that might disconcert an observer accustomed to the kind of developments that were then taking place in western countries.

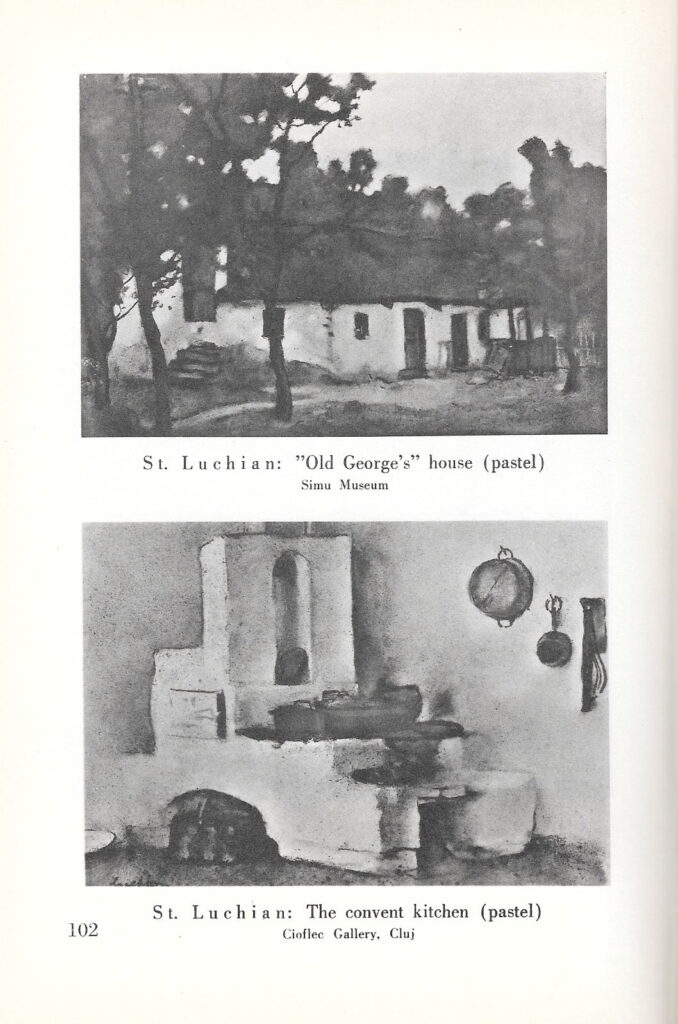

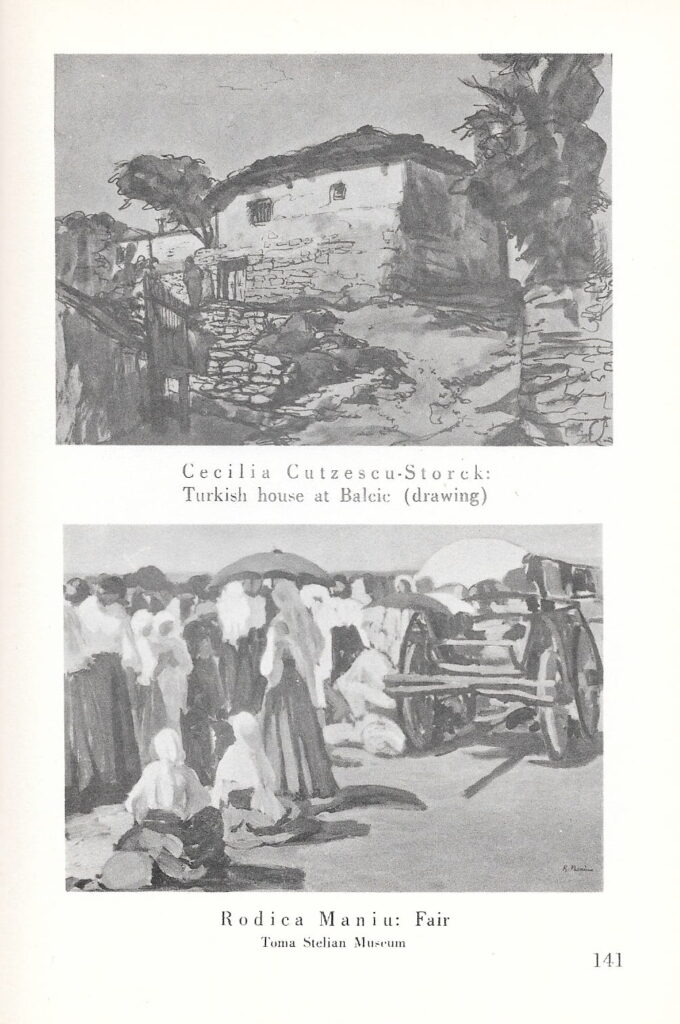

His first chapter frames this shift in terms of a ‘spiritual reawakening’ that separated the older generation (bowed down by ‘Turkish domination’ and ‘underhand connections with the foreigner, Russian or Austrian’, their ‘intrigues’, ‘selfish scheming’ and ‘mental sloth’) from ‘the children of these same men … possessed of a burning patriotism, aspiring to freedom and eager for social justice, imbued with the political and literary ideas of the West’.[4] This is followed by a discussion of what he calls the early ‘primitives and pioneers’ who, in the first half of the nineteenth century, laid the groundwork for the emergence of a distinctive ‘Romanian school’ in the second half. According to Oprescu, this was initiated by Teodor Aman (1831-91) and found its most successful representatives in the Barbizon-trained painters Ion Andreescu (1850-82) and Nicolae Grigorescu (1838-1907) who fused French painterly language with a Romanian poetic sensibility. Their success opened the door to a younger school of colourists, most notably Ștefan Luchian (1868-1916), followed by a raft of ‘contemporary’ artists whose diverse practice ranged from traditional academicism to international modernism.

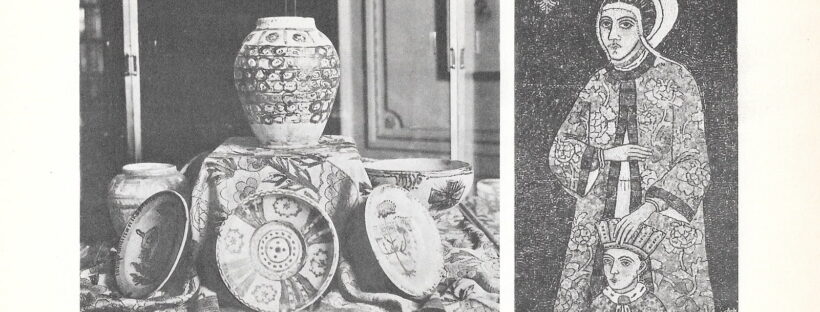

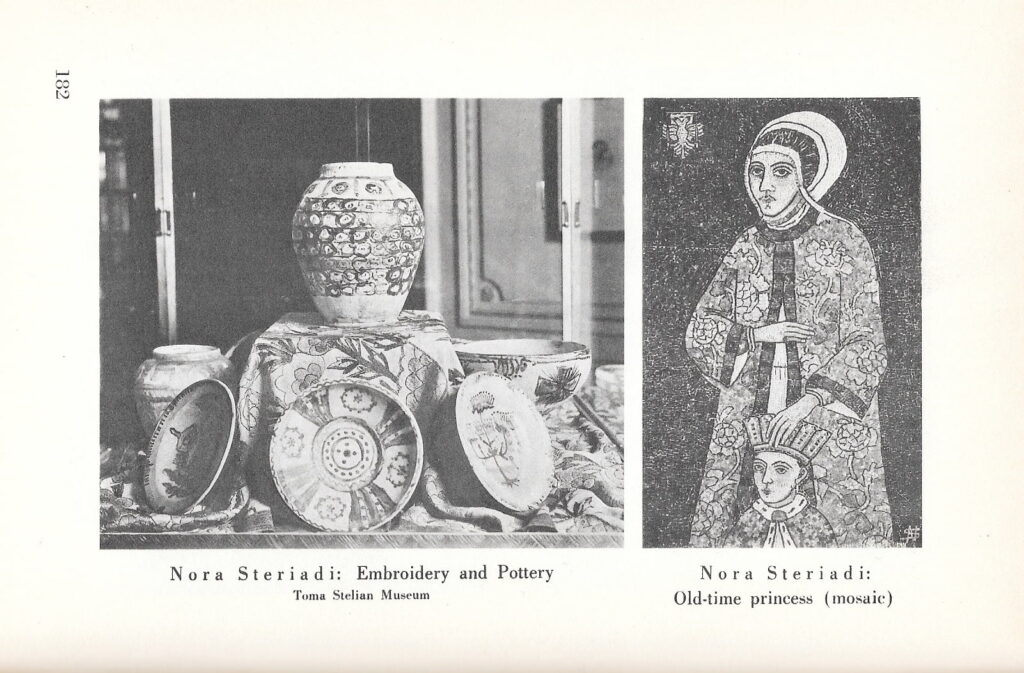

Oprescu was clearly slightly wary of the latter, excusing the former Zurich Dadaist Marcel Iancu and the Expressionist-Constructivist artist Max Herman Maxy (both key figures of the Bucharest avant-garde) as follows: ‘Marcel Iancu and Maxy represent more revolutionary tendencies, softened, however, and made acceptable by a touch of irony and a singular blend of colours’.[5] Tellingly, he does not recognise Maxy’s significant role (together with Andrei Vespremie) in the development of a modern Academy of Decorative Arts in Bucharest,[6] stating that ‘in the field of the applied arts we have produced rather little’, and favouring instead the vernacularising pottery, embroidery and mosaics of Nora Steriadi.[7] This is understandable: Oprescu was a driving force in the interwar period’s vigorous intellectual interest in the Romanian peasant and produced an important publication on the subject for the London-based decorative arts magazine The Studio in 1929 (also in St Andrews’ Library).[8] But it is also symptomatic of the critical divide that seems to have emerged between Bucharest’s internationalist, largely Jewish-led avant-garde and ideologically-motivated ‘official’ narratives of what constituted ‘Romanian’ identity in art following the creation of Greater Romania after the First World War.

Central to this narrative was the idea of a native artistic ‘sensibility’ that linked Byzantine and folk art with the modern forms of contemporary Romanian artists. This was clearly articulated by Oprescu in his conclusion to Roumanian Art where he argued for continuity of ‘soul and outlook’ and explained that the Romanian love of colour, ‘an ancient inheritance, born of an intimacy with nature’ and expressed by peasant art through the centuries, exemplified the innate artistic ‘feeling’ linking past and present art forms.[9] This was a narrative also fostered by Oprescu’s close friend, the leading French art historian Henri Focillon, in his catalogue article for the 1925 Exhibition of Romanian Art in Paris. The intellectual and personal friendship between Focillon and Oprescu was significant for the development of the ideas of both. While Oprescu showed a clear affinity with the formalist approach articulated in Vie des formes, Focillon (who built up a fine collection of Romanian folk art) shared Oprescu’s desire to widen the definition of ‘art’ to include work hitherto considered to belong to ethnography. Together they helped organise the 1928 International Congress of Folk Arts and Folklore in Prague. Here Oprescu, who had been Secretary of the League of Nations’ International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation since 1923, promoted an internationalist vision of folk art as reflective of a wider human condition that transcended political geography and could help post-war efforts to build bridges between cultures.

It was with a similar desire to foster international relationships that Oprescu took part in the Thirteenth International Congress of Art History in Stockholm in 1933. The congress had the ambitious aim of extending the reach of art history to all territories and, as such, took as its theme ‘national schools’. Yet, as Carmen Popescu has argued, this actually resulted in a hierarchical mapping of art, framed in terms of the ‘great’ nations which produced ‘universal’ styles, and the ‘little’ nations which assimilated and ‘nationalised’ them. It is a cartography of centre and periphery that Art History still wrestles with today. The result, according to Popescu, was that ‘all the speakers from the “peripheries” strove to demonstrate, firstly, that their art constituted a national school and, secondly, to justify its belonging to the great family of art’.[10] Oprescu’s book, written on the back of this conference and gifted to Baxter, is one such example.

There is no record of whether Baxter, whose own scholarly interests lay in much earlier periods, ever used the book; he certainly donated it to the University Library within a couple of years. His goal in fostering Romanian contacts seems to have been to extend his international network of Byzantine scholars, and also to acquire local help in arranging practical issues. Princess Martha Bibescu, for example, writing in 1937 from the Quai de Bourbon in Paris, intervened on his behalf with the Romanian Ministry of Communication concerning a financial matter. Reminiscing about her visit to the Istanbul excavations in May of the previous year, she thanked Baxter for sending a copy of the report on the Great Palace dig that he had published in The Times in 1935 and which had stirred up a fair level of public excitement. [11]

The most important Byzantine scholar with whom Baxter crossed paths in Bucharest was Nicolae Iorga (1871-1940), historian, literary critic, playwright, former Prime Minister and eminent Byzantinist, who had organised the first International Congress of Byzantine Studies in 1924. Baxter met him in 1936, a year after the publication of Iorga’s famous study Byzance après Byzance, when he participated in a historical congress in Bucharest and visited Iorga’s home. He also seems to have charmed Milena Iacob, the librarian of Iorga’s Institute of Byzantine Studies, who made him a gift of a valuable embroidered Romanian blouse and wrote an effusively admiring letter, now in the St Andrews archive.[12] Other letters in the archive indicate that Baxter travelled fairly widely within Romania (including a visit organised by the British Council to a Dr Luttinger in Cernăuți [Czernowitz] in April 1936[13]), and corresponded with scholars such as Constantin Marinescu, Professor of Medieval History at the University of Cluj (Kolozsvár).

Baxter’s Romanian interactions should be seen within the context of his wider Balkan networking activities and his extensive correspondence with key scholars in Sofia, Belgrade, London, Copenhagen and beyond. He used his position at St Andrews to further his interests in Istanbul: in 1938, when the Walker Trust’s excavation permit was due to expire, Baxter proposed Bay Fethi Okyar, the Turkish ambassador in London, for an honorary degree from the University. He was supported by Steven Gaselee, librarian and keeper of the papers at the Foreign Office in London, who was also the British literary agent of Romania’s Queen Marie. The manoeuvre worked and the permit was renewed for a further two years.[14]

It was presumably in the context of one of these visits to Bucharest between 1936-38 that Baxter met Oprescu and received his book. By this stage Oprescu, although Secretary of the Committee of Arts and Letters in Geneva, was returning more frequently to Romania, where Iorga had appointed him Professor of Art History at Bucharest University in 1931. He was also involved in the work of the Institut Français in Bucharest which he had helped Focillon to found in 1924. The Institute played a central role in diplomatic efforts to expand cultural exchanges between the two countries, attracting key French intellectual figures such as Roland Barthes who came as its librarian in 1947.[15] Barthes, like Oprescu, was homosexual; while Barthes was able to leave Bucharest in 1949 with the tightening of Soviet control, Oprescu had to forge a working relationship with the new regime which may to some degree have used his homosexuality as a means of coercion.[16] Despite the Securitate reports filed by fellow art historian and informer Petru Comarnescu, Oprescu managed to maintain his position as Director of the Institute of Art History, even using the Institute to support cultural figures persecuted by the new regime.[17] Ioana Apostol has argued that the Securitate eventually closed Oprescu’s file believing that he was ‘merely too stubborn to be ideologically disciplined’.[18]

Baxter, meanwhile, was facing problems of his own. Kouneni explains that, as war loomed, Baxter was dismissed by Russell from direction of the Great Palace project (citing his inability to get on with fellow archaeologists) and didn’t author the final report of the excavations published in 1947. During the War, the British Council and Steven Runciman (then Professor of Byzantine History and Art at the University of Istanbul) were given curatorship of the site, with David Talbot Rice of Edinburgh University taking over for the final seasons from 1952-54.[19]

It is unlikely that Baxter and Oprescu were able to maintain intellectual links after the Iron Curtain descended. Certainly, no further evidence of correspondence has yet come to light. Since 1939 Oprescu’s book has remained quietly in St Andrews’ Library, rarely borrowed save by me as a PhD student in the 1990s. If Romania itself has yet to find a place in the global turn of art history now taught in western universities, then at least Oprescu’s early attempt to disseminate knowledge of Romanian art internationally, by planting books – the vehicles of this dissemination – in foreign collections, can now be recognised for the role it played in the rich pre-socialist nexuses of transnational intellectual exchange.

[1] George Oprescu, Roumanian Art from 1800 to Our Days, Malmö: A.-B. Malmö Ljustrycksanstalt, 1935, p. 9.

[2] It followed Nicolae Iorga’s very brief account of western influence on nineteenth-century Romanian art in the epilogue of L’Art roumain du XIVe au XIXe siècle (Paris: E. de Boccard, 1922) and Jean Cantacuzène’s (Ioan Cantacuzino’s) essay ‘La Peinture Moderne’ in the catalogue of the Exposition d’art roumain ancien et moderne, Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris: Georges Petit, 1925.

[3] Lenia Kouneni, ‘“By Scottish Munificence”: The Walker Trust Excavations of the Great Palace in Istanbul, 1931-34’, forthcoming in Discovering Byzantium in Istanbul: Scholars, Institutions, and Challenges (1800-1955), Istanbul Research Institute, 2021. I am grateful to Dr Kouneni for generously allowing me to read an unpublished draft of her article, as well as for help finding Romanian material in the Baxter archive.

[4] Oprescu, p. 11.

[5] Oprescu, p. 51.

[6] See Alexandra Chiriac’s doctoral thesis, Putting the Peripheral Centre Stage: performing modernism in interbellum Bucharest 1924-34, University of St Andrews, 2019.

[7] Oprescu, p. 54.

[8] George Oprescu, Peasant Art in Roumania, Special Autumn Number of The Studio, London: Herbert Reiach, 1929.

[9] Oprescu (1935), pp. 60-61.

[10] Carmen Popescu, ‘“Cultures majeures, cultures mineures”. Quelques réflexions sur la (géo)politisation du folklore dans l’entre-deux-guerres’, in Spicilegium. Studii și articole în onoarea Prof. Corina Popa, București: UNArte, 2015, p. 236.

[11] Letters from Princess Marthe Bibesco to Baxter, 14 and 27 January 1937, University of St. Andrews Library, Special Collections, Box 1937-39, folder 1. The report was entitled: J. H. Baxter, ‘The Secrets of Byzantium’, The Times (London), 26 and 28 October 1935.

[12] Letter from Milena Iacob to Baxter, 9 May 1936, University of St Andrews Library, Special Collections, ms36944/– [1936]. This was a generous and symbolic present: the Romanian blouse (or ia) was one of the most appreciated pieces of Romanian folk art in Western Europe, coveted by collectors, sold in modern reinvention by Liberty’s, publicised by Queen Marie and immortalised in Matisse’s 1940 painting ‘La blouse roumaine’.

[13] Letter from K. R. Johnstone of the British Council to Baxter, 2 April 1936, University of St Andrews Library, Special Collections, ms36944/345.

[14] Kouneni, p. 26. Gaselee himself owned a signed copy of Queen Marie’s book Why? A Story of Great Longing, that he donated to Cambridge University Library.

[15] See Alexandru Matei, ‘Barthes en Roumanie: histoire et amour, expériences pathétiques’, Romance Studies, Vol. 34, Issue 3-4, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1080/02639904.2017.1308072

[16] Unlike his contemporary Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș, who was stripped of his academic positions and died in penury, Oprescu managed to maintain a relationship with the new authorities and was appointed Director of the Institute of Art History, founded in 1949 as one of several new research institutes under the auspices of the Romanian Academy. He remained in this role until his death in 1969. In 1992 it was renamed the George Oprescu Institute of Art History.

[17] See Lucian Boia (ed.), Dosarele secrete ale agentului Anton. Petru Comarnescu în arhivele Securității, București: Humanitas, 2014.

[18] Ioana Apostol, ‘“Cercetătorul” în atenția securității: G. Oprescu în arhivele C.N.S.A.S.’, Studii și Cercetări de Istoria Artei. Artă plastică, Tome 7 (51), 2017, p. 161.

[19] Kouneni, pp. 30-37. The report was entitled The Great Palace of the Byzantine Emperors: Being a First Report on Excavations Carried Out in Istanbul on Behalf of the Walker Trust (The University of St Andrews), 1935-38, Oxford: OUP, 1947.

Art Historiographies in Central and Eastern Europe

Art Historiographies in Central and Eastern Europe