SEE MORE DETAILS AND APPLY HERE.

Author: cosmin

Cosmin Minea will present this Friday his paper, ‘The transnational creation of the Romanian national architectural heritage in the nineteenth century.’ at the international conference ‘Space, Art and Architecture between East and West: The Revolutionary Spirit’, Athens. Watch it on youtube at 11.15 CET.

Click here for the official booklet of the conference

- The audience will be able to join us on the Hellenic Open University Channel on YouTube, where the conference will be live- streamed here.

Anna Adashinskaya has presented her paper “Pious Offerings to Meteora Monasteries (1348-1420s): Between Political Representation, Family Belonging, and Personal Agency” at the 23rd International Graduate Conference of the Oxford University Byzantine Society.

To access the conference booklet, visit: https://oxfordbyzantinesociety.files.wordpress.com/2021/02/oubs2021_booklet.pdf

The general link of the conference is here: https://oxfordbyzantinesociety.wordpress.com/international-graduate-conference-2021/

From Bucharest to Byzantium: the entangled history of a Romanian art history book in St Andrews University Library

A signed copy of George Oprescu’s 1935 book Roumanian Art from 1800 to our Days in St Andrews University Library reveals fascinating links between Scottish and Romanian academics in the interwar period.

Shona Kallestrup

______

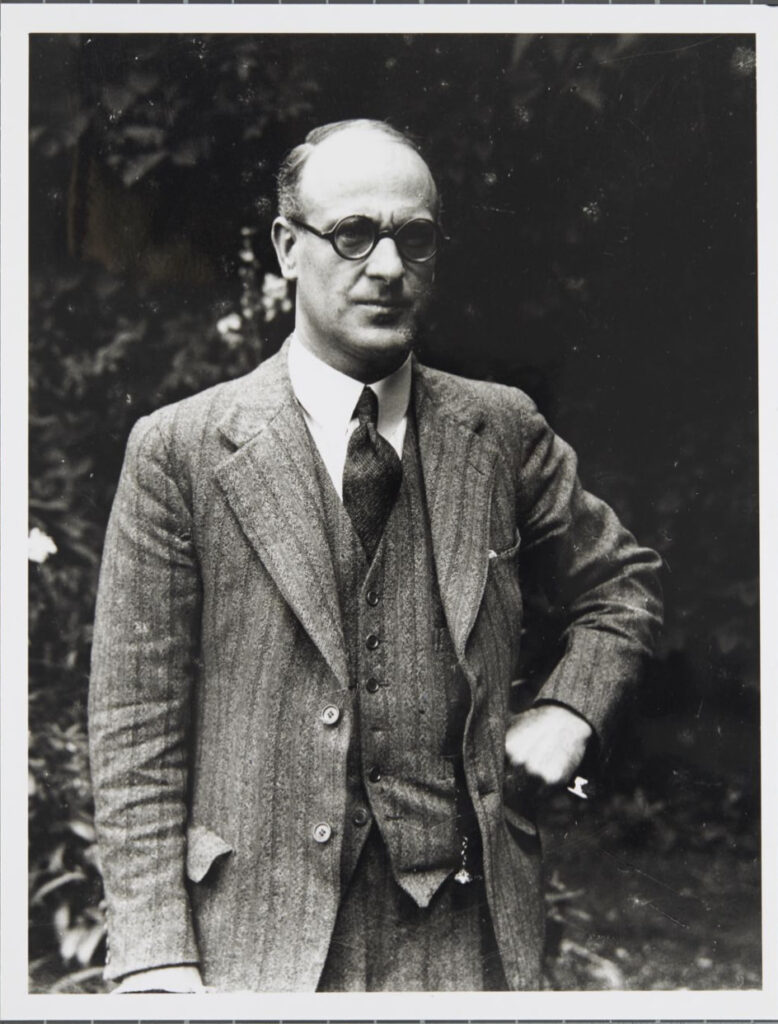

Among the few books on Romanian art in the library of St Andrews University is a signed copy of George Oprescu’s Roumanian Art from 1800 to Our Days, published in 1935 in Malmö. Oprescu (1881-1969) was one of Romania’s most important art historians; he held the Chair of Art History at the University of Bucharest and founded the Institute of Art History (part of the Romanian Academy) which today bears his name. This English translation of his book, together with the original French version, was commissioned by the Swedish editor John Kroon who had met Oprescu at the 1933 International Congress of Art History in Stockholm and persuaded him ‘to give a conspectus of the artistic movement in Roumania in the XIXth and XXth Centuries’.[1] It represented the third attempt (and the first in English) to present modern Romanian art to an international public,[2] and comprises a short, fifty-page, summary essay, followed by an extensive photo catalogue divided into painting, sculpture and architecture. Important both for the rich number of images made available to a western audience for the first time, and for the significant presence of women artists (nine painters, five sculptors and one architect), Oprescu’s short volume was one of the very few internationally-accessible publications on modern Romanian art before the ideological rupture of communism distorted art historical scholarship on the pre-socialist period.

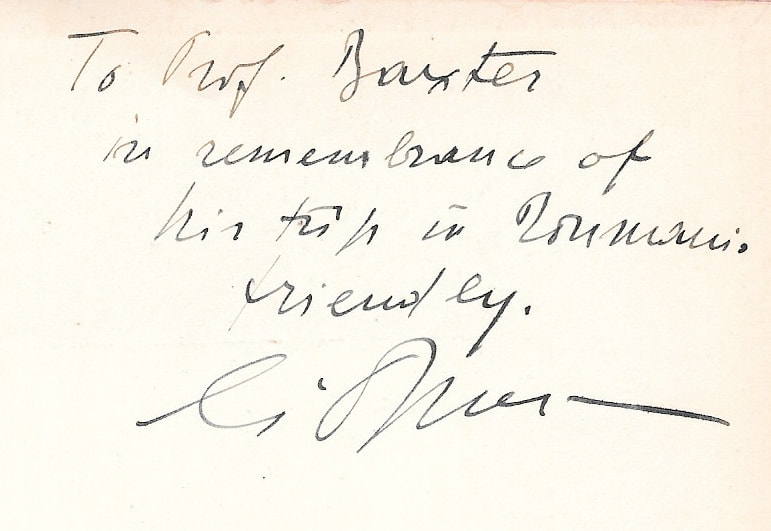

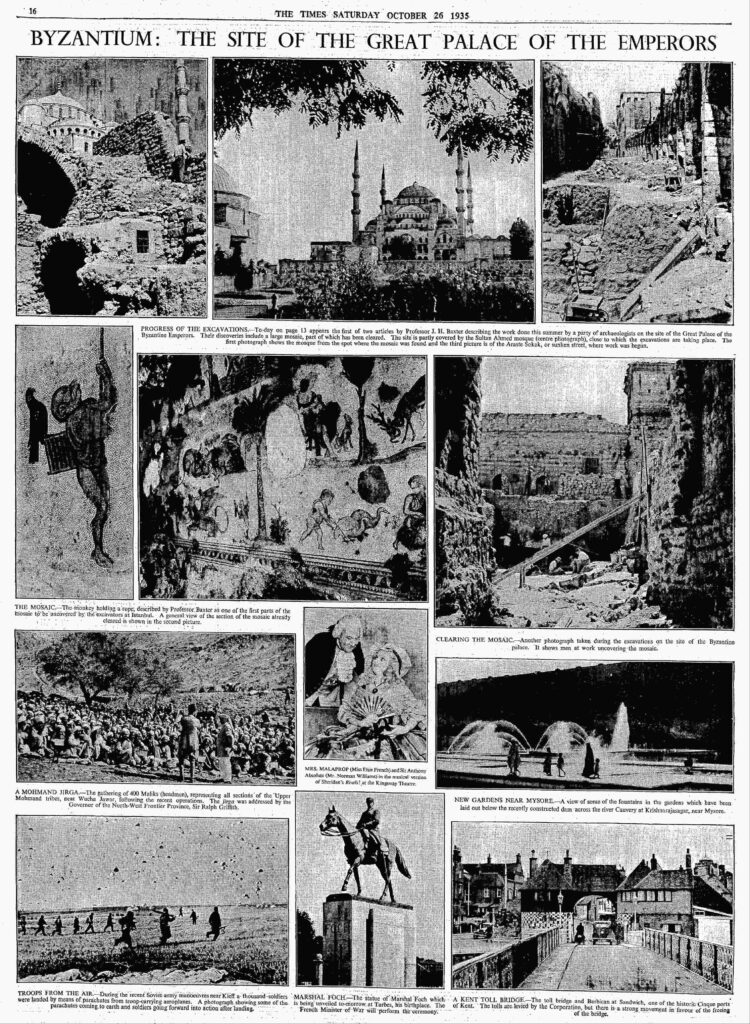

The St Andrews volume carries an inscription on the first page: ‘To Prof. Baxter in remembrance of his trip in Roumania. Friendly, G. Oprescu’, together with a presentational label to the library from ‘Professor J. H. Baxter, DLitt, etc, 1939’. James Houston Baxter (1894-1973) held the Chair of Ecclesiastical History at St Andrews from 1922-70. He is most famously remembered for the series of excavations of the Great Palace of the Byzantine Emperors in Constantinople that he conducted for the Walker Trust between 1933-39. Recent research by Dr Lenia Kouneni of the School of Art History at St Andrews has revealed the curious story of the spiritualist underpinnings of this venture, which originated as a paranormal quest to find the remains of Justinian’s Library. Funded by the Markinch paper-mill owner David Russell, via the Walker Trust that his great uncle had set up to support the University, the excavations were the result of Russell’s friendship with the neo-Christian mystic Major Wellesley Tudor Pole, who had ‘discovered’ the purported location of Justinian’s Library through spiritualist séances with Russian exiles in Paris. Professor Baxter, with the weight of St Andrews University behind him, was subsequently engaged to give a legitimate academic front to the enterprise. Luckily for Russell and Baxter, the excavations – although finding no evidence of the Library – very quickly came upon an extensive, mosaic-paved peristyle hall, today considered one of the finest material discoveries of imperial Byzantium.[3]

It was in the course of Baxter’s journeys to and from Istanbul that he regularly passed through Romania en route to cross the Black Sea from the port of Constanța. He made contact with several of the most important Romanian intellectual figures of the day: together with Oprescu these included the leading historian, eminent Byzantinist and (from 1931-32) Romanian Prime Minister, Nicolae Iorga; as well as the famous writer Princess Martha Bibescu. Barely a decade, then, before the descent of the Iron Curtain severed Romania’s complex cultural and political links with Western Europe, Baxter found himself part of a rich transnational network of intellectual exchange that stretched from the Balkans to Scandinavia, evidence of which is preserved today in his correspondence in the St Andrews archives and in the books he donated to the library. Taking Oprescu’s art historical gift as a starting point, this blog will briefly explore some key points that emerge from the entangled history of the Romanian scholar and the St Andrews Byzantinist.

First, let us place Oprescu’s book in its art historiographical context. Art History only really emerged as a self-confident discipline in Romania in the 1920s with the work of scholars like Oprescu, Iorga, Alexandru Țzigara-Samurcaș and Coriolan Petranu. This, in turn, was a result of the widescale adoption of western academic frameworks that accompanied Romania’s emergence as an independent state and rapid re-orientation from Oriental to Occidental models in the nineteenth century. This abrupt volte-face had brought with it the introduction of western easel painting, sculptural traditions and beaux-arts architecture, together with the academies and salons that supported them. Yet the country’s longer historical artistic evolution, characterised by a strong Byzantine and folk tradition, did not fit comfortably into the art historical models developed in Western and Central Europe. Romanian art historians struggled with the problem of how to bridge the cultural caesura of the nineteenth century and link the religious art of the past with the very different forms of modern secular painting, sculpture and architecture. Oprescu explained that his book was an attempt, therefore,

to throw into relief the circumstances, outward or subjective, which surround and explain the development of the Roumanian school […] in a word all the various features that might disconcert an observer accustomed to the kind of developments that were then taking place in western countries.

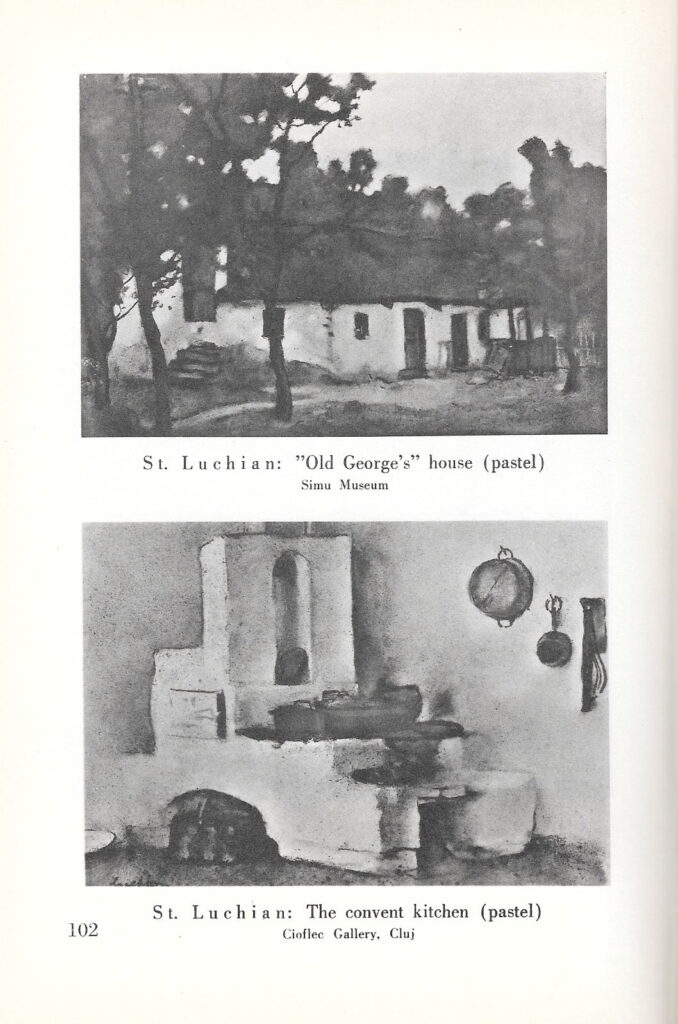

His first chapter frames this shift in terms of a ‘spiritual reawakening’ that separated the older generation (bowed down by ‘Turkish domination’ and ‘underhand connections with the foreigner, Russian or Austrian’, their ‘intrigues’, ‘selfish scheming’ and ‘mental sloth’) from ‘the children of these same men … possessed of a burning patriotism, aspiring to freedom and eager for social justice, imbued with the political and literary ideas of the West’.[4] This is followed by a discussion of what he calls the early ‘primitives and pioneers’ who, in the first half of the nineteenth century, laid the groundwork for the emergence of a distinctive ‘Romanian school’ in the second half. According to Oprescu, this was initiated by Teodor Aman (1831-91) and found its most successful representatives in the Barbizon-trained painters Ion Andreescu (1850-82) and Nicolae Grigorescu (1838-1907) who fused French painterly language with a Romanian poetic sensibility. Their success opened the door to a younger school of colourists, most notably Ștefan Luchian (1868-1916), followed by a raft of ‘contemporary’ artists whose diverse practice ranged from traditional academicism to international modernism.

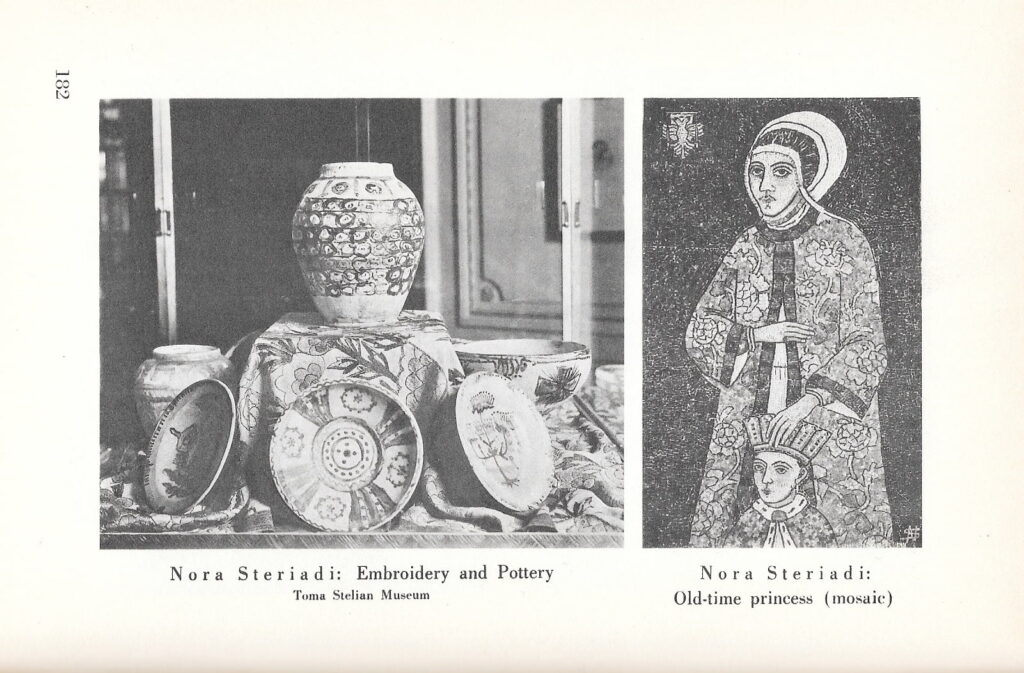

Oprescu was clearly slightly wary of the latter, excusing the former Zurich Dadaist Marcel Iancu and the Expressionist-Constructivist artist Max Herman Maxy (both key figures of the Bucharest avant-garde) as follows: ‘Marcel Iancu and Maxy represent more revolutionary tendencies, softened, however, and made acceptable by a touch of irony and a singular blend of colours’.[5] Tellingly, he does not recognise Maxy’s significant role (together with Andrei Vespremie) in the development of a modern Academy of Decorative Arts in Bucharest,[6] stating that ‘in the field of the applied arts we have produced rather little’, and favouring instead the vernacularising pottery, embroidery and mosaics of Nora Steriadi.[7] This is understandable: Oprescu was a driving force in the interwar period’s vigorous intellectual interest in the Romanian peasant and produced an important publication on the subject for the London-based decorative arts magazine The Studio in 1929 (also in St Andrews’ Library).[8] But it is also symptomatic of the critical divide that seems to have emerged between Bucharest’s internationalist, largely Jewish-led avant-garde and ideologically-motivated ‘official’ narratives of what constituted ‘Romanian’ identity in art following the creation of Greater Romania after the First World War.

Central to this narrative was the idea of a native artistic ‘sensibility’ that linked Byzantine and folk art with the modern forms of contemporary Romanian artists. This was clearly articulated by Oprescu in his conclusion to Roumanian Art where he argued for continuity of ‘soul and outlook’ and explained that the Romanian love of colour, ‘an ancient inheritance, born of an intimacy with nature’ and expressed by peasant art through the centuries, exemplified the innate artistic ‘feeling’ linking past and present art forms.[9] This was a narrative also fostered by Oprescu’s close friend, the leading French art historian Henri Focillon, in his catalogue article for the 1925 Exhibition of Romanian Art in Paris. The intellectual and personal friendship between Focillon and Oprescu was significant for the development of the ideas of both. While Oprescu showed a clear affinity with the formalist approach articulated in Vie des formes, Focillon (who built up a fine collection of Romanian folk art) shared Oprescu’s desire to widen the definition of ‘art’ to include work hitherto considered to belong to ethnography. Together they helped organise the 1928 International Congress of Folk Arts and Folklore in Prague. Here Oprescu, who had been Secretary of the League of Nations’ International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation since 1923, promoted an internationalist vision of folk art as reflective of a wider human condition that transcended political geography and could help post-war efforts to build bridges between cultures.

It was with a similar desire to foster international relationships that Oprescu took part in the Thirteenth International Congress of Art History in Stockholm in 1933. The congress had the ambitious aim of extending the reach of art history to all territories and, as such, took as its theme ‘national schools’. Yet, as Carmen Popescu has argued, this actually resulted in a hierarchical mapping of art, framed in terms of the ‘great’ nations which produced ‘universal’ styles, and the ‘little’ nations which assimilated and ‘nationalised’ them. It is a cartography of centre and periphery that Art History still wrestles with today. The result, according to Popescu, was that ‘all the speakers from the “peripheries” strove to demonstrate, firstly, that their art constituted a national school and, secondly, to justify its belonging to the great family of art’.[10] Oprescu’s book, written on the back of this conference and gifted to Baxter, is one such example.

There is no record of whether Baxter, whose own scholarly interests lay in much earlier periods, ever used the book; he certainly donated it to the University Library within a couple of years. His goal in fostering Romanian contacts seems to have been to extend his international network of Byzantine scholars, and also to acquire local help in arranging practical issues. Princess Martha Bibescu, for example, writing in 1937 from the Quai de Bourbon in Paris, intervened on his behalf with the Romanian Ministry of Communication concerning a financial matter. Reminiscing about her visit to the Istanbul excavations in May of the previous year, she thanked Baxter for sending a copy of the report on the Great Palace dig that he had published in The Times in 1935 and which had stirred up a fair level of public excitement. [11]

The most important Byzantine scholar with whom Baxter crossed paths in Bucharest was Nicolae Iorga (1871-1940), historian, literary critic, playwright, former Prime Minister and eminent Byzantinist, who had organised the first International Congress of Byzantine Studies in 1924. Baxter met him in 1936, a year after the publication of Iorga’s famous study Byzance après Byzance, when he participated in a historical congress in Bucharest and visited Iorga’s home. He also seems to have charmed Milena Iacob, the librarian of Iorga’s Institute of Byzantine Studies, who made him a gift of a valuable embroidered Romanian blouse and wrote an effusively admiring letter, now in the St Andrews archive.[12] Other letters in the archive indicate that Baxter travelled fairly widely within Romania (including a visit organised by the British Council to a Dr Luttinger in Cernăuți [Czernowitz] in April 1936[13]), and corresponded with scholars such as Constantin Marinescu, Professor of Medieval History at the University of Cluj (Kolozsvár).

Baxter’s Romanian interactions should be seen within the context of his wider Balkan networking activities and his extensive correspondence with key scholars in Sofia, Belgrade, London, Copenhagen and beyond. He used his position at St Andrews to further his interests in Istanbul: in 1938, when the Walker Trust’s excavation permit was due to expire, Baxter proposed Bay Fethi Okyar, the Turkish ambassador in London, for an honorary degree from the University. He was supported by Steven Gaselee, librarian and keeper of the papers at the Foreign Office in London, who was also the British literary agent of Romania’s Queen Marie. The manoeuvre worked and the permit was renewed for a further two years.[14]

It was presumably in the context of one of these visits to Bucharest between 1936-38 that Baxter met Oprescu and received his book. By this stage Oprescu, although Secretary of the Committee of Arts and Letters in Geneva, was returning more frequently to Romania, where Iorga had appointed him Professor of Art History at Bucharest University in 1931. He was also involved in the work of the Institut Français in Bucharest which he had helped Focillon to found in 1924. The Institute played a central role in diplomatic efforts to expand cultural exchanges between the two countries, attracting key French intellectual figures such as Roland Barthes who came as its librarian in 1947.[15] Barthes, like Oprescu, was homosexual; while Barthes was able to leave Bucharest in 1949 with the tightening of Soviet control, Oprescu had to forge a working relationship with the new regime which may to some degree have used his homosexuality as a means of coercion.[16] Despite the Securitate reports filed by fellow art historian and informer Petru Comarnescu, Oprescu managed to maintain his position as Director of the Institute of Art History, even using the Institute to support cultural figures persecuted by the new regime.[17] Ioana Apostol has argued that the Securitate eventually closed Oprescu’s file believing that he was ‘merely too stubborn to be ideologically disciplined’.[18]

Baxter, meanwhile, was facing problems of his own. Kouneni explains that, as war loomed, Baxter was dismissed by Russell from direction of the Great Palace project (citing his inability to get on with fellow archaeologists) and didn’t author the final report of the excavations published in 1947. During the War, the British Council and Steven Runciman (then Professor of Byzantine History and Art at the University of Istanbul) were given curatorship of the site, with David Talbot Rice of Edinburgh University taking over for the final seasons from 1952-54.[19]

It is unlikely that Baxter and Oprescu were able to maintain intellectual links after the Iron Curtain descended. Certainly, no further evidence of correspondence has yet come to light. Since 1939 Oprescu’s book has remained quietly in St Andrews’ Library, rarely borrowed save by me as a PhD student in the 1990s. If Romania itself has yet to find a place in the global turn of art history now taught in western universities, then at least Oprescu’s early attempt to disseminate knowledge of Romanian art internationally, by planting books – the vehicles of this dissemination – in foreign collections, can now be recognised for the role it played in the rich pre-socialist nexuses of transnational intellectual exchange.

[1] George Oprescu, Roumanian Art from 1800 to Our Days, Malmö: A.-B. Malmö Ljustrycksanstalt, 1935, p. 9.

[2] It followed Nicolae Iorga’s very brief account of western influence on nineteenth-century Romanian art in the epilogue of L’Art roumain du XIVe au XIXe siècle (Paris: E. de Boccard, 1922) and Jean Cantacuzène’s (Ioan Cantacuzino’s) essay ‘La Peinture Moderne’ in the catalogue of the Exposition d’art roumain ancien et moderne, Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris: Georges Petit, 1925.

[3] Lenia Kouneni, ‘“By Scottish Munificence”: The Walker Trust Excavations of the Great Palace in Istanbul, 1931-34’, forthcoming in Discovering Byzantium in Istanbul: Scholars, Institutions, and Challenges (1800-1955), Istanbul Research Institute, 2021. I am grateful to Dr Kouneni for generously allowing me to read an unpublished draft of her article, as well as for help finding Romanian material in the Baxter archive.

[4] Oprescu, p. 11.

[5] Oprescu, p. 51.

[6] See Alexandra Chiriac’s doctoral thesis, Putting the Peripheral Centre Stage: performing modernism in interbellum Bucharest 1924-34, University of St Andrews, 2019.

[7] Oprescu, p. 54.

[8] George Oprescu, Peasant Art in Roumania, Special Autumn Number of The Studio, London: Herbert Reiach, 1929.

[9] Oprescu (1935), pp. 60-61.

[10] Carmen Popescu, ‘“Cultures majeures, cultures mineures”. Quelques réflexions sur la (géo)politisation du folklore dans l’entre-deux-guerres’, in Spicilegium. Studii și articole în onoarea Prof. Corina Popa, București: UNArte, 2015, p. 236.

[11] Letters from Princess Marthe Bibesco to Baxter, 14 and 27 January 1937, University of St. Andrews Library, Special Collections, Box 1937-39, folder 1. The report was entitled: J. H. Baxter, ‘The Secrets of Byzantium’, The Times (London), 26 and 28 October 1935.

[12] Letter from Milena Iacob to Baxter, 9 May 1936, University of St Andrews Library, Special Collections, ms36944/– [1936]. This was a generous and symbolic present: the Romanian blouse (or ia) was one of the most appreciated pieces of Romanian folk art in Western Europe, coveted by collectors, sold in modern reinvention by Liberty’s, publicised by Queen Marie and immortalised in Matisse’s 1940 painting ‘La blouse roumaine’.

[13] Letter from K. R. Johnstone of the British Council to Baxter, 2 April 1936, University of St Andrews Library, Special Collections, ms36944/345.

[14] Kouneni, p. 26. Gaselee himself owned a signed copy of Queen Marie’s book Why? A Story of Great Longing, that he donated to Cambridge University Library.

[15] See Alexandru Matei, ‘Barthes en Roumanie: histoire et amour, expériences pathétiques’, Romance Studies, Vol. 34, Issue 3-4, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1080/02639904.2017.1308072

[16] Unlike his contemporary Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș, who was stripped of his academic positions and died in penury, Oprescu managed to maintain a relationship with the new authorities and was appointed Director of the Institute of Art History, founded in 1949 as one of several new research institutes under the auspices of the Romanian Academy. He remained in this role until his death in 1969. In 1992 it was renamed the George Oprescu Institute of Art History.

[17] See Lucian Boia (ed.), Dosarele secrete ale agentului Anton. Petru Comarnescu în arhivele Securității, București: Humanitas, 2014.

[18] Ioana Apostol, ‘“Cercetătorul” în atenția securității: G. Oprescu în arhivele C.N.S.A.S.’, Studii și Cercetări de Istoria Artei. Artă plastică, Tome 7 (51), 2017, p. 161.

[19] Kouneni, pp. 30-37. The report was entitled The Great Palace of the Byzantine Emperors: Being a First Report on Excavations Carried Out in Istanbul on Behalf of the Walker Trust (The University of St Andrews), 1935-38, Oxford: OUP, 1947.

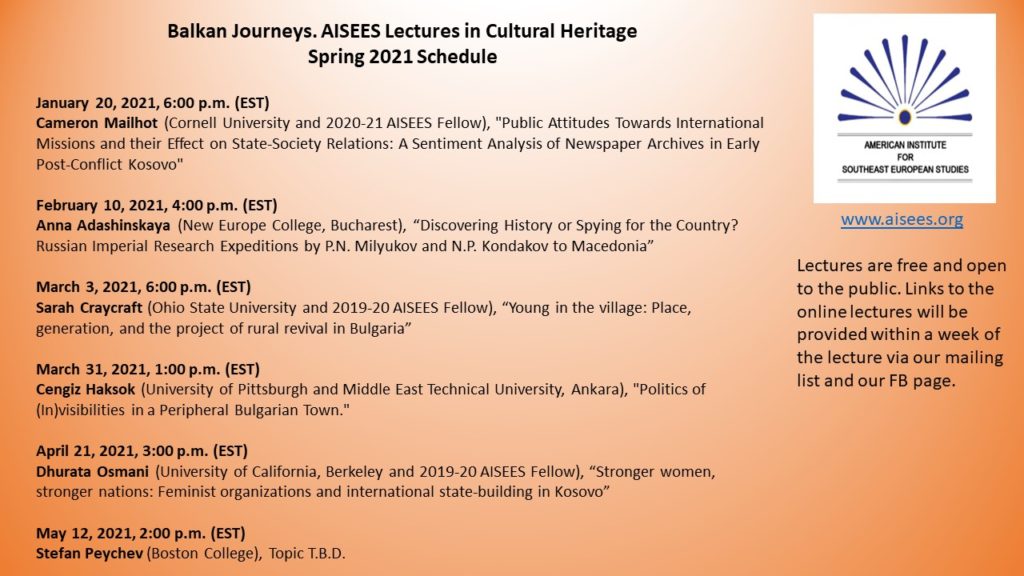

Anna Adashinskaya will give a talk at the AISEES Spring Lecture Series on February 10th, 4:00 p.m. (EST), titled “Discovering History or Spying for the Country? Russian Imperial Research Expeditions by P.N. Milyukov and N.P. Kondakov to Macedonia”

February 10, 2021, 4:00 p.m. (EST)

Anna Adashinskaya (New Europe College, Bucharest). “Discovering History or Spying for the Country? Russian Imperial Research Expeditions by P.N. Milyukov and N.P. Kondakov to Macedonia”

Lectures are free. For the link, follow https://aisees.org/ or https://www.facebook.com/AISEESorg

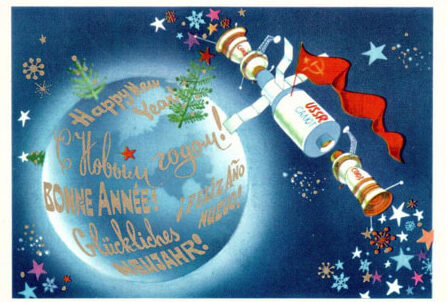

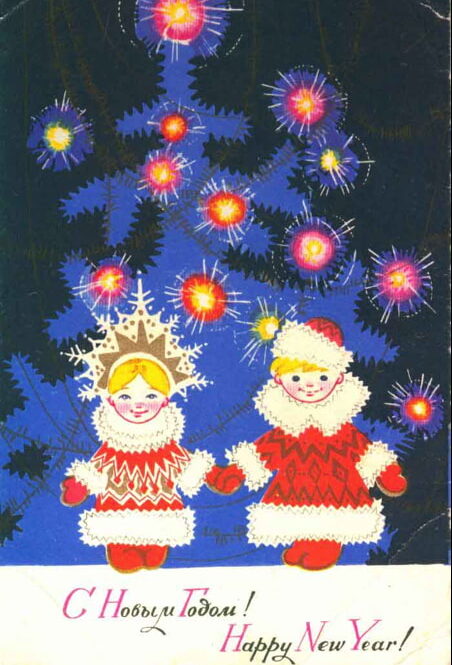

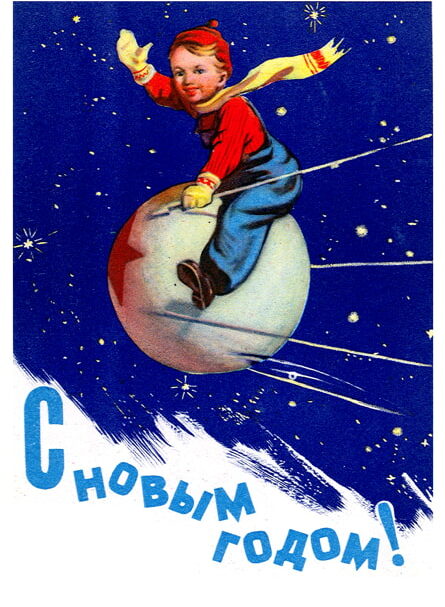

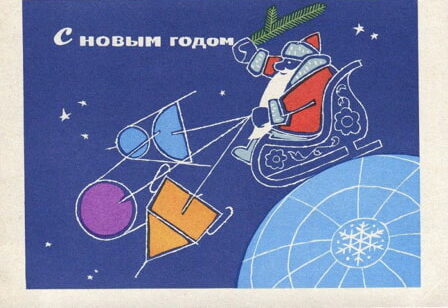

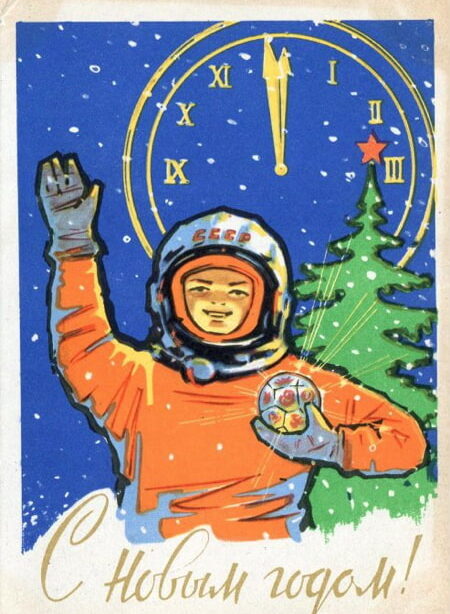

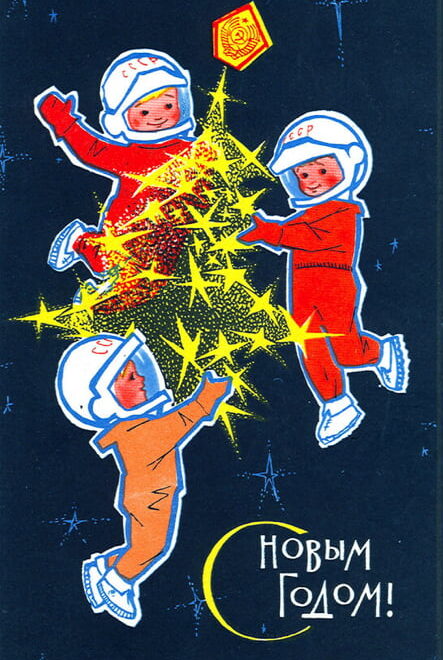

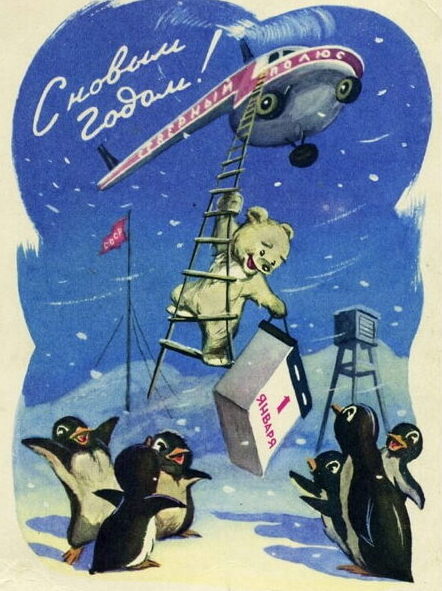

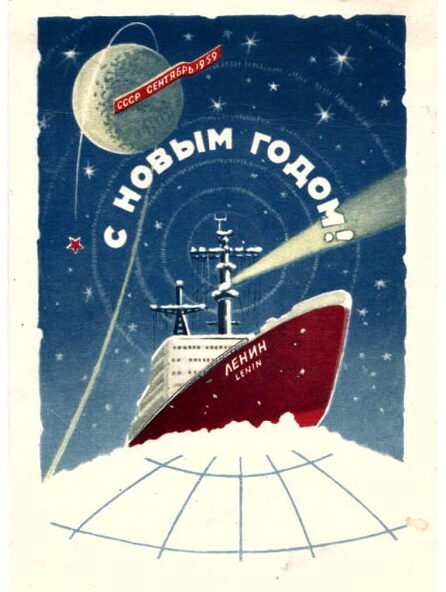

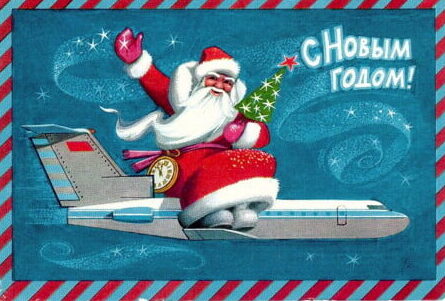

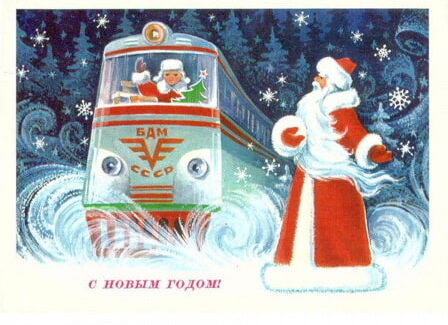

From: Russia with (Winter) Love. Russian Postcards Celebrating the Winter Holidays. To: You

Anna Adashinskaya

This overview of Soviet postcards for the festive winter season shows how political and economic concerns translate into some intriguing postcard designs that include World War 2 themes, the adventure of the Soviet Grandfather Frost or the Great Soviet Industry.

The old custom of Christmas letters in England caused problems for the prominent London inventor, Henry Cole. He couldn’t leave the messages unanswered, but found them too numerous to deal with all at once. During the holiday season of 1843, this anxious gentleman came up with a solution. He commissioned an acquaintance, the artist J.C. Horsley, to make a sketch depicting a family at the festive table, accompanied by a generic Christmas greeting. The image, printed in a thousand copies for Mr Cole’s friends and families, became the first Christmas card sent via the British postal system.

In Russia, Christmas postcards appeared only at the end of the 19th century. The first open letters (without illustrations) were put into circulation on 1 January 1872 and their production was initially a state prerogative. The State Paper Procurement Expedition specifically printed them for the main church celebrations. However, the refined Petersburg and Moscovite public also commissioned postcards from private artists or photographers, and delivered them via couriers, sidestepping the Imperial Post.

On the majority of the Christmas cards of this era, one may see scenes from the Gospels, angels, various animals and young children. Though many talented painters aspired to create elegant festive pictures, Elisabeth Boehm (1843-1914) became the most popular postcard illustrator. Her small watercolors featured sugary images of children wearing traditional Russian dresses, accompanied by folk proverbs and celebratory wishes. Famous Russian art critic Vladimir Stasov (1824-1906) praised Boehm for her “original scenes of Russian life,” while grateful customers offered to sponsor the printing of her designs.

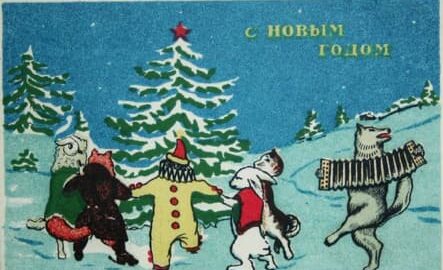

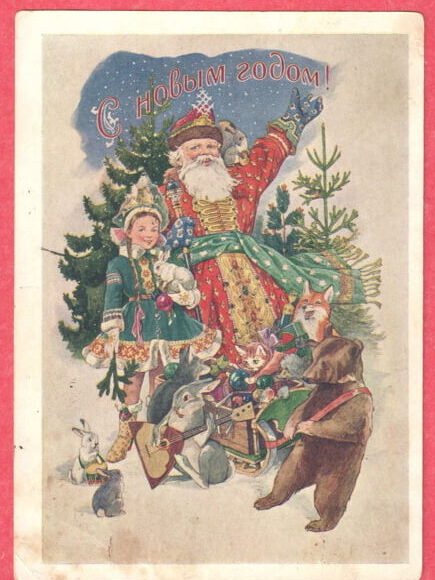

After the 1917 Revolution, Christmas celebrations were banned as inappropriate for the new atheist society, and the tradition of exchanging postcards temporarily ceased. Christmas customs received a second life in 1935, however, when the USSR established New Year as an alternative winter feast. Old Christmas personages underwent secularization as well, as Soviet cultural discourse appropriated and transformed their confessional belonging, but essentially their functions and attributes remained the same. The protagonists of the feast received new identities found in Slavic pre-Christian narratives, such as songs or fairy tales: St. Nicholas became the folklore Grandfather Frost (Ded Moroz) and the infant Jesus was transformed into the Young Year Toddler. Soon other symbols gained new interpretations: the Bethlehem star changed its colour to red and became an emblem of the Red Army. The cast of animals became localized as well: the traditional cow, donkey and sheep of the Nativity were replaced by Russian taiga creatures (wolfs, bears, foxes, deers, and hares), engaged in the transportation and ornamentation of the New Year tree. In January 1937, in the spirit of Soviet women’s emancipation, Grandfather Frost received a female co-worker, the Snow Maiden (Snegurochka). Gradually, all these new attributes of the Soviet winter holidays made their way onto the postcards exchanged by USSR citizens via the new, fast-delivery Post. These mobile pictures were perfectly suited to the popularization of the new imagery; published in large print runs, they reached the most remote corners of the country in a matter of days.

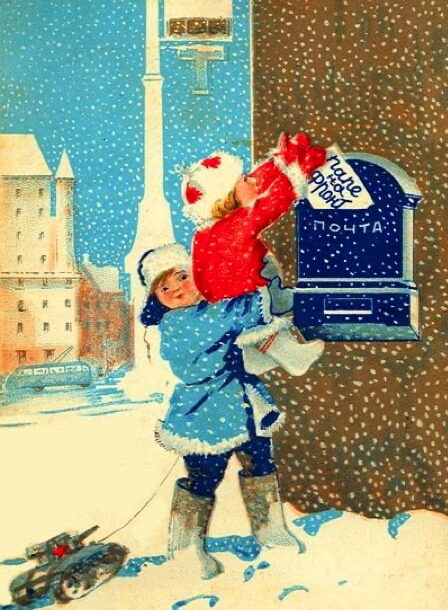

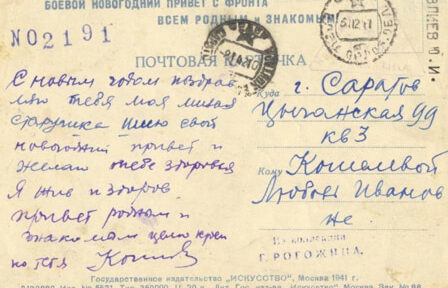

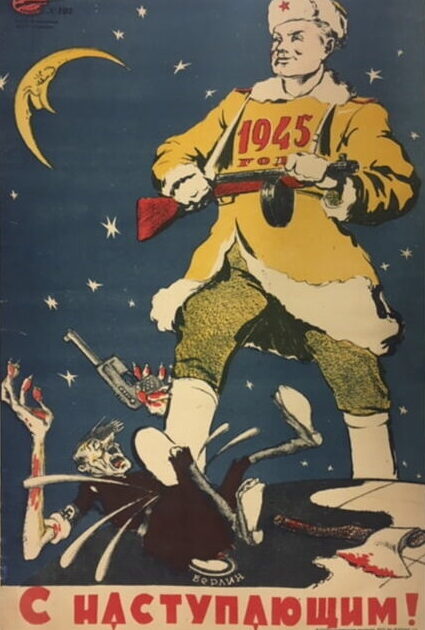

The New Year postcards changed their designs and messages following the start of the Second World War. Rapid correspondence exchange with the army became a truly strategic issue, on a par with purely military tasks such as the supply of weapons and cartridges. The Soviet Post strove to deliver mails even to and from the Front and partisan units. During wartime, postcard editions were specifically designed for every annual celebration, though the quality of paper and colours declined. In one of the most difficult periods of the war, during the Battle of Moscow in October-November 1941, the publishing house Art issued a freshly designed set of New Year’s greetings with a circulation of 300.000 copies. These new images contained patriotic messages reminding soldiers of their duty to the country, nation, and family. WWII New Year postcards roughly fall into two main categories, those sent from home and greetings from soldiers to their families and friends. The former often pictured children sending letters “for Daddy at the Front!” and women working “for Victory, for the Army,” while soldiers’ postcards usually depicted troops in winter uniform and typical New Year characters assisting the Soviets in battle. Thus, Grandfather Frost became a bearded sailor destroying the hated Nazis with missiles launched from his gift sack.

Soldiers seemed to appreciate the very possibility of using a postcard instead of normal paper. Its cheery colourfulness and different texture created a much-needed feeling of festivity within the daily military routine. In a postcard from the Contemporary Russian History Museum, an unknown Soviet soldier highlighted the unusual beauty of the postal medium to his recipients:

My dear ones! You see, how beautiful the paper is that I am using to write to you! We received these cards to celebrate the New Year. I congratulate you and kiss you warmly. I won’t be able to greet this New Year with you. Well, we’ll greet the next one together. Drink, each of you, a full glass for me, and for all our chaps who are fighting the German bastard at the Front. It must of course be a full glass! And filled with good wine! I wish you a happy and kind New Year for 1942. And we will do our best here. At the moment our chaps are beating the Germans hard, and in ’42 we will be even stronger.” (New Year’s Eve of 1 January, 1942).

Towards the end of the War, depictions of the coming New Year became associated with the advance of the Soviet Army, as the Russians used the same verbal forms in both phrases, the “coming year” and “the advancing army”. This linguistic polysemy caused the appearance of a postcard design depicting the New Year as a victorious Red Army soldier.

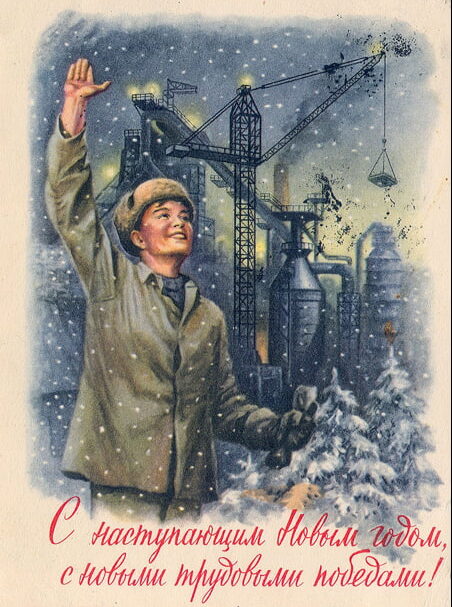

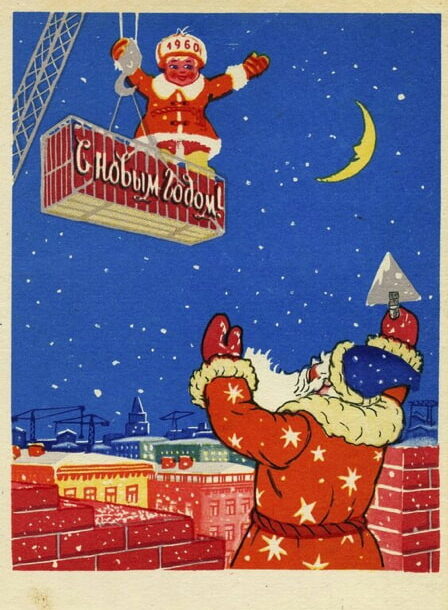

Mass reconstruction projects distinguished the post war era, with several million Soviet citizens sent to build houses, factories, roads, and railways. Consequently, the imagery of New Year cards changed as well. Now, the Young Year Toddler and Grandfather Frost turned into workers and engineers. They operated loading cranes and managed oil refineries to create a better future for the Soviet people.

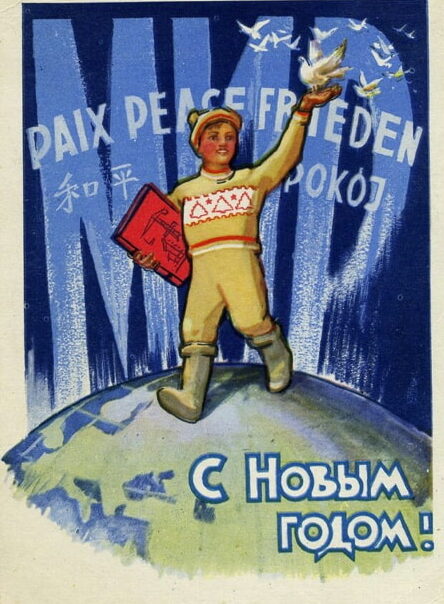

After the War, the USSR replace the doctrine of “world revolution” with the policy of “peaceful coexistence”, acknowledging capitalist states’ right to exist and facilitating international collaboration. Around the same time, the main Soviet publishing house for fine arts, IZOGIZ, initiated a new series of festive postcards. They featured the achievements of the country’s foreign policy and underlined the peaceful and international character of the communist state. Thus, with the USSR representing itself as a guarantor of international peace, the Soviet Young Year Toddler walked on the Earth, bringing peace to various nations.

During the Khrushchev Thaw, Soviet citizens began to make international contacts. In July 1957, the Sixth World Festival of Youth and Students took place in Moscow, attracting 34.000 people from 130 states. The festival came at the height of attempts to “raise the Iron Curtain slightly”: for the first time, many foreigners came to the country, and some of them established friendly relations with Russians. The people of the USSR strove to maintain a correspondence with their foreign friends for decades, and the publishing house Soviet Artist (Sovetskiy hudozhnik) assisted this task by issuing postcards with foreign language greetings and international postage stamps.

In people’ consciousness, the New Year offered a promise of change and novelty, and was closely associated with new hopes and expectations. Soviet cinema staged New Year’s Eve as a joyful communal celebration where different classes came together to wish “New happiness” to each other. Following this thrust for innovation, the visual tradition started to depict the main technological and cultural discoveries of the outgoing year on New Year postcards.

These closely followed developments in the Soviet space programme and every December a new element of space exploration found its way into the designs commissioned by the Soviet Post, the Ministry of Communication, or the Transportation Ministry. In 1957, when the USSR launched the first artificial Earth satellite, the theme of spaceships burst into the postcard world. Initially, artists had to craft their own imaginary depictions of rockets, as original images and photos were strictly classified. By the New Year of 1958, however, anyone could buy a postcard featuring the Sputnik. By 1962, three satellites orbited the planet, and Grandfather Frost rode them instead of the traditional horse Troika. On 12 April 1961, Yuri Gagarin made the first flight into space in the Vostok-1 spacecraft. That year, Soviet citizens recognized his historic orange SK-1 spacesuit on the congratulatory images printed by the Soviet Post. In 1965, the first ever spacewalk inspired the New Year postcard of 1966, where three little boy astronauts dance around a star tree in outer space.

The cold of the Arctic and Antarctic was well-suited to winter festivities and so too the Soviet ideology of promoting achievements in science and technology by means of such popular media as congratulatory postcards. After many decades working in the Arctic, Soviet researchers decided to apply their experience to the ice of Antarctica, and, in 1956, the First Composite Soviet Antarctic Expedition left Leningrad to reach the southernmost continent. That year’s postcards celebrated this exchange of polar expertise by issuing New Year images where the “indigenous population” of the northern seas, the polar bears, met their southern counterparts, the penguins. A little later, in September 1959, the Soviet Union launched the world’s first nuclear-powered icebreaker, Lenin. Even before completing its naval tests, the icebreaker was already featured on postcards celebrating the arrival of 1960.

New Year cards also reacted to USSR successes in civil aviation and railways. For example, in 1973, Grandfather Frost rode the Yak-40, the world’s first turbojet passenger aircraft for local transportation, and a year later, could also be seen flying the Il-62, the first Soviet long-haul jetliner operating intercontinental flights. In the 1970s, Grandfather Frost assisted young KomSoMol workers constructing the Baikal–Amur Mainline (BAM), which stretched nearly 3250 km from Lake Baikal to the Soviet Pacific coast. Given the difficult terrain, the construction of the BAM presented an engineering challenge: almost half of the route ran through permafrost, where winter temperatures could plummet to −60° C. However, that clearly didn’t pose a problem for the traditional winter characters.

The decline of Soviet ideology paralleled a growth of consumerist society, and New Year postcards began to echo the new concerns of the nation. Sugary and sentimental pictures of children and animals, together with the very concept of Christmas, made their way back into print. As the late-Soviet population dreamed of satiety and comfort, so traditional New Year wishes started to be accompanied by images of festive tables, laden with champagne, exotic fruits, and expensive desserts. And caviar became the main achievement of the outgoing year…

Shona Kallestrup is Speaker at the AAH ANNUAL PUBLIC LECTURE | RE-WRITING WOMEN INTO ART HISTORY

ANNUAL PUBLIC LECTURE | RE-WRITING WOMEN INTO ART HISTORY

3 December 2020, 7 – 8.15pm BST, Online

This event will take a fresh look at women as collectors, patrons, exhibition organisers and museum founders in Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Until recently, women’s contributions in these areas has been undervalued, not keeping up with the attention and critical recognition that women artists have received. Our three speakers will consider the achievements of some extraordinary and fascinating women in the art world whose accomplishments are less well known than their male counterparts of the period, though are equally significant.

The event will be hosted by Sandi Toksvig and will feature three, fifteen-minute talks by the speakers followed by a panel discussion. Presentations will include the following:

Meaghan Clarke, Senior Lecturer in Art History, University of Sussex

While women are invariably absent in institutional histories of this period, the elusive records of temporary exhibitions indicate that women were active cultural agents. Fair Women was the historical equivalent of a ‘blockbuster’ exhibition. Organised by a committee of women, this exhibition of portraits of women and decorative objects opened in 1894 to great fanfare at the Grafton Galleries in London. It coincided with the emergence of the independent New Woman in novels, plays and the press. In looking nostalgically back to previous models of female behaviour, the exhibition has been seen as a ‘slap in the face’ for the New Woman. However, on closer examination Fair Women complicated assumptions about the representation of women and the superficiality of female collectors and art patrons. Women were celebrated for their ‘wit and intellect’, and the show revealed an important network of collectors, patrons and ‘New’ women.

Shona Kallestrup, Associate Lecturer, School of Art History, University of St Andrews

The charismatic Queen Marie of Romania (1875-1938) was an amateur artist, writer and collector of unusual tastes. Arriving in Romania in 1893, this British-born princess acted as a conduit for transnational artistic exchange, aligning herself with the breakaway Bucharest group ‘Artistic Youth’ and cultivating an international network of contacts that included the American dancer Loïe Fuller with whom she made a ballet and film. With her talent for public media strategy, Marie crafted a vision of monarchy which at times shocked her British relatives, but placed her at the heart of the Romanian national ideal. Central to her success was the distinctive visual culture she curated in a series of extraordinary palace interiors filled with collections of Art Nouveau, Byzantine and peasant art. Widely disseminated as photographs and postcards, these served as powerful performative settings for Marie to act out her successive roles as a Princesse Lointaine, wartime saviour and ‘Mother of all the Romanians’.

Elizabeth Emery, Professor of French, Dept of World Languages and Cultures, Montclair State University

The Musée d’Ennery, the first free public museum of Asian art in Paris (opened in 1908), owes its existence to a young woman, Clémence Lecarpentier (1823-1898), who began collecting small sculpted objects related to Far Eastern mythology in the 1840s. At her death in 1898, she bequeathed her collection, which had grown to nearly 7,000 objects to the French state, along with the house whose galleries she had designed to showcase it. Despite the fact that she was praised by contemporaries for her pioneering work as a collector of Far Eastern sculpted and ceramic objects, and despite the existence of archives that clearly document her fifty-year engagement with the collection, scholars continue to present this remarkable house museum either as the work of her wealthy husband, playwright Adolphe d’Ennery, or as a joint venture. The elision of Clémence Lecarpentier Desgranges d’Ennery’s agency from cultural memory derives from complicated social factors, among them women’s legal status in France, nationalism, classism, and a sexism that persists in marketing materials that characterize the collection as a “jewel box,” an “opulent time capsule,” or as a “cabinet of curiosity.”

The panel discussion will be moderated by Thomas Stammers, Associate Professor (Modern European Cultural History) in the Department of History, Durham University.

Join us online for this FREE event, book your ticket via Eventbrite.

CALL FOR PAPERS: Space, Art and Architecture Between East and West: The Revolutionary Spirit

Details on the following link:

CALL FOR PAPERS: Design. Design History, Research Methodology and Institutions

(click on the ‘English’ tab on the right)

https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/aq/announcement/view/435

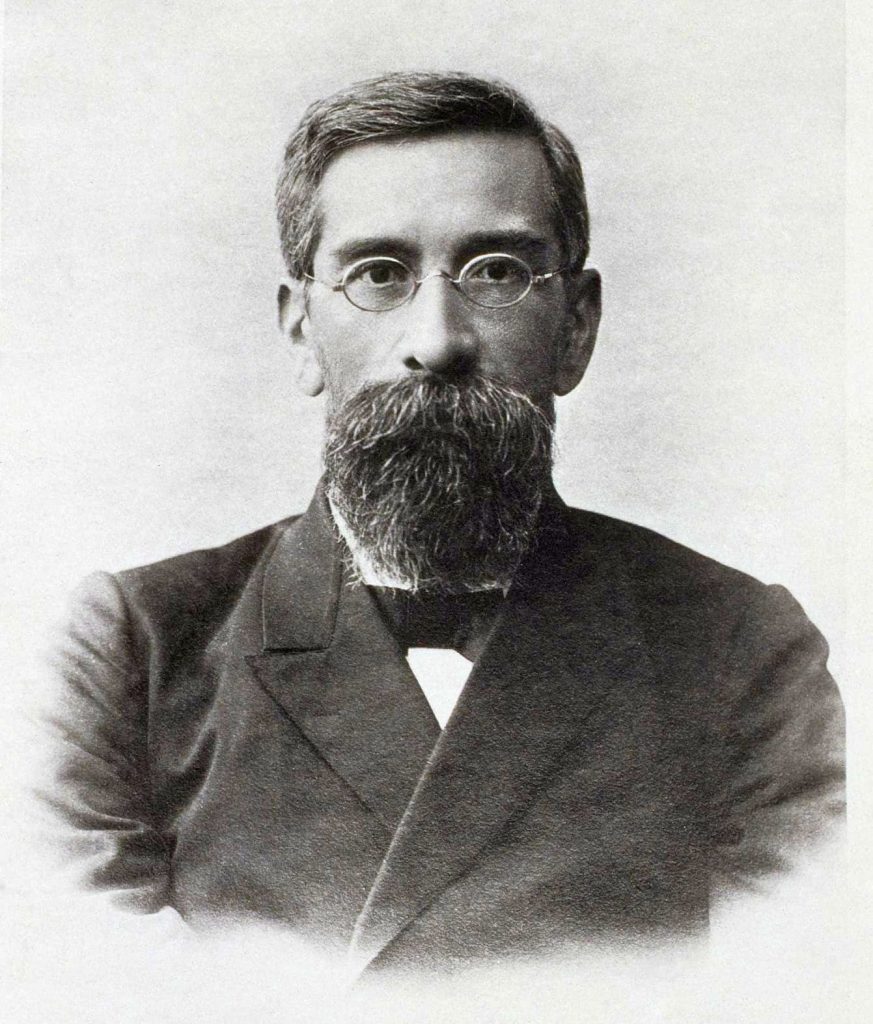

An “Ancient Argonaut” in the Service of the Empire: the Research Expeditions of Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov

Anna Adashinskaya

An acclaimed art historian, professor, museum curator, tireless traveler and reluctant spy: these were the social roles played by the pioneer of the iconographic method in Russia, Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov. Every time he needed to finance a costly expedition to distant Byzantine monuments, he faced a dilemma: to spy or not to spy?

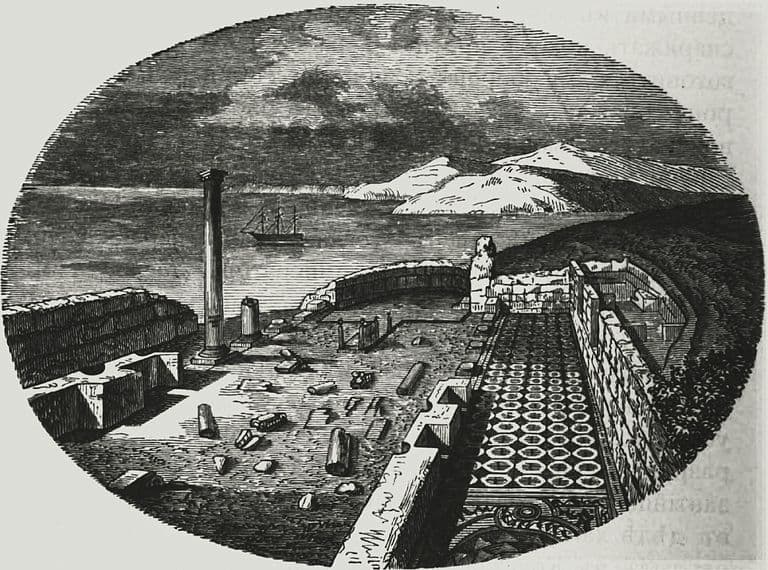

Before the middle of the nineteenth century, Russian archeological expeditions were primarily private enterprises. The founding father of Russian archeological studies, Count Aleksey Uvarov, excavated the medieval basilica on the site of ancient Chersonesos in Crimea. However, instead of preserving the monument intact, he extracted parts of the mosaics, which were later embedded in the floor of a room in the New Hermitage Palace. The main purpose of the excavations and field research, it seems, was the decoration of royal residences and the enrichment of the collection of the Hermitage as the personal museum of the Russian tsars.

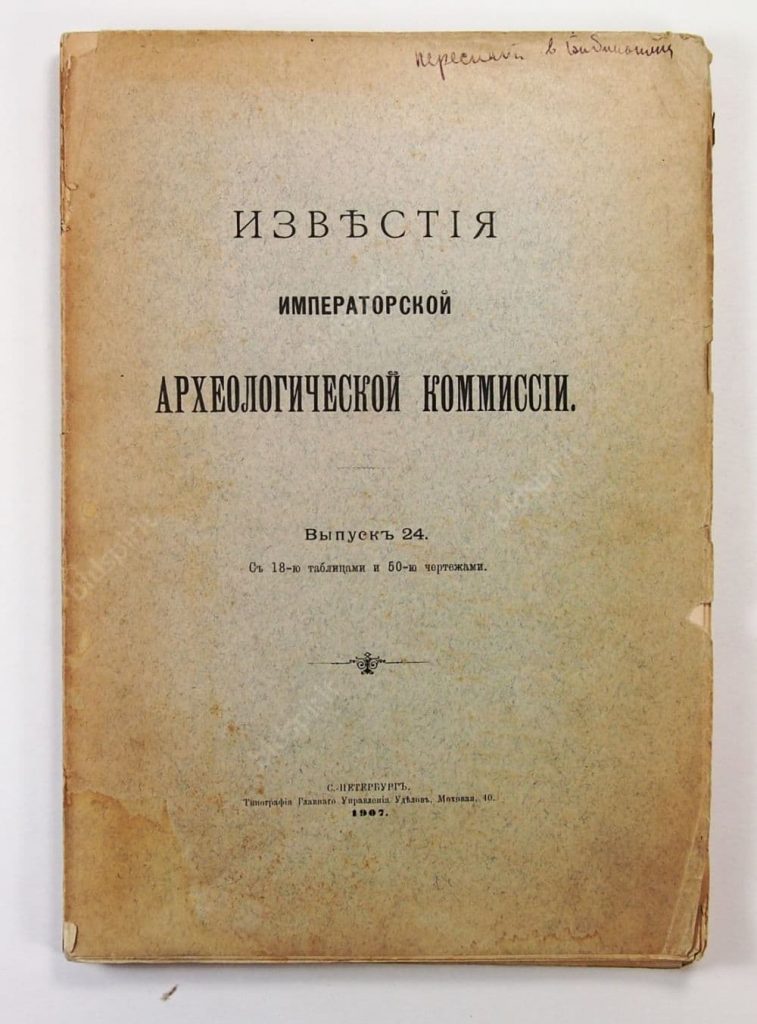

In 1859, the increase in the scale of archaeological works led to the establishment of the Imperial Archaeological Commission. Control over archaeological activities in Russia was thus assigned to the Ministry of the Imperial Court, in whose department the Commission worked. The Commission issued special permits for fieldwork and sponsored research expeditions, but not very generously. In addition, it published annual illustrated reports, later called Izvestiya Archeologicheskoi Komissii (Reports of the Archaeological Commission) and became a periodical providing detailed information about excavations, collections of antiquities, and research expeditions.

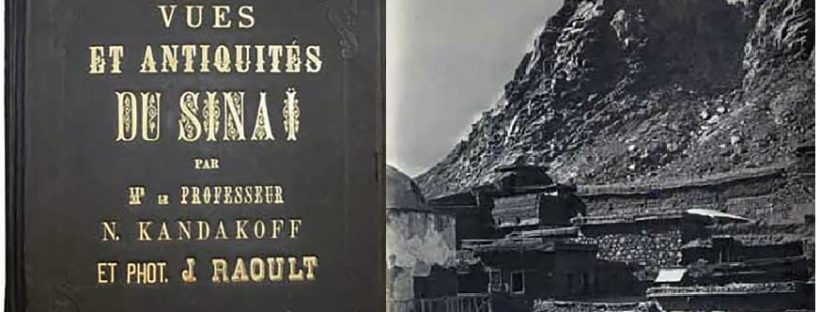

Nonetheless, expeditions to foreign countries were rarely sponsored by the state. In 1881, Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov (1844-1925) undertook a research trip to Sinai, setting, in his words, “purely archaeological goals.”[1] He wanted to compile a catalogue of the monastic antiquities and publish it as photographs. Kondakov paid for this trip himself and also financed the report’s publication, as no higher authorities were interested into sponsoring the distant journey of a young scholar working at Odessa University. During the trip, he collected about 1,500 photos taken by the photographer J.C. Raoult who accompanied him. This was an unusually large corpus of monument images, and for several decades it continued to circulate in the form of a published album which contained original photographs, (rather than typographically printed pages), alongside a written description of the trip (the number of prints in each album varied from 100 to 117).

This volume was the first photographically illustrated publication on St. Catherine’s Monastery and its rich collections. Through it, Kondakov introduced the Sinai antiquities to international scholarship and acquainted the European public with the monastery’s architecture, icon-painting, and manuscripts. Prior to this edition, researchers had only had access to drawings, which could not give an accurate idea of the medieval objects. For his work on the Sinai Album, Raoult was awarded the Order of St. Stanislav of the III degree, while Kondakov received the Lomonosov Prize in 1883. This trip made the scholar famous and contributed to his academic promotion to a position at the Hermitage Museum.

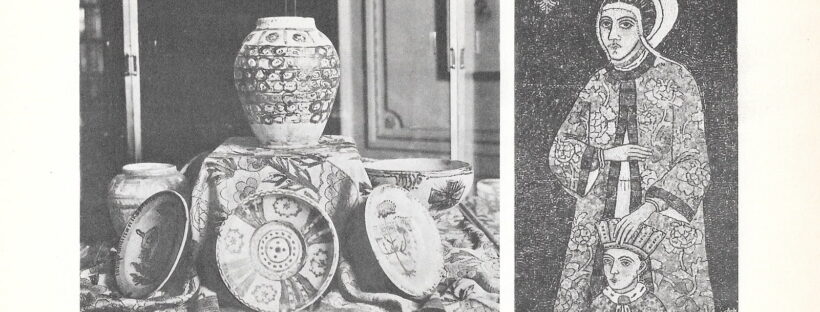

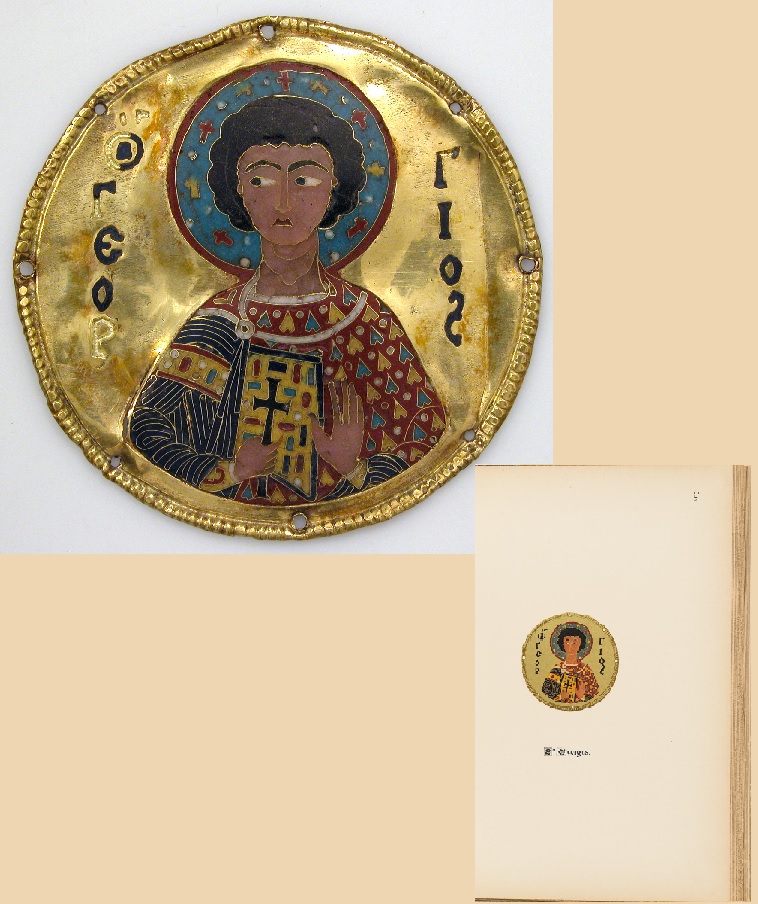

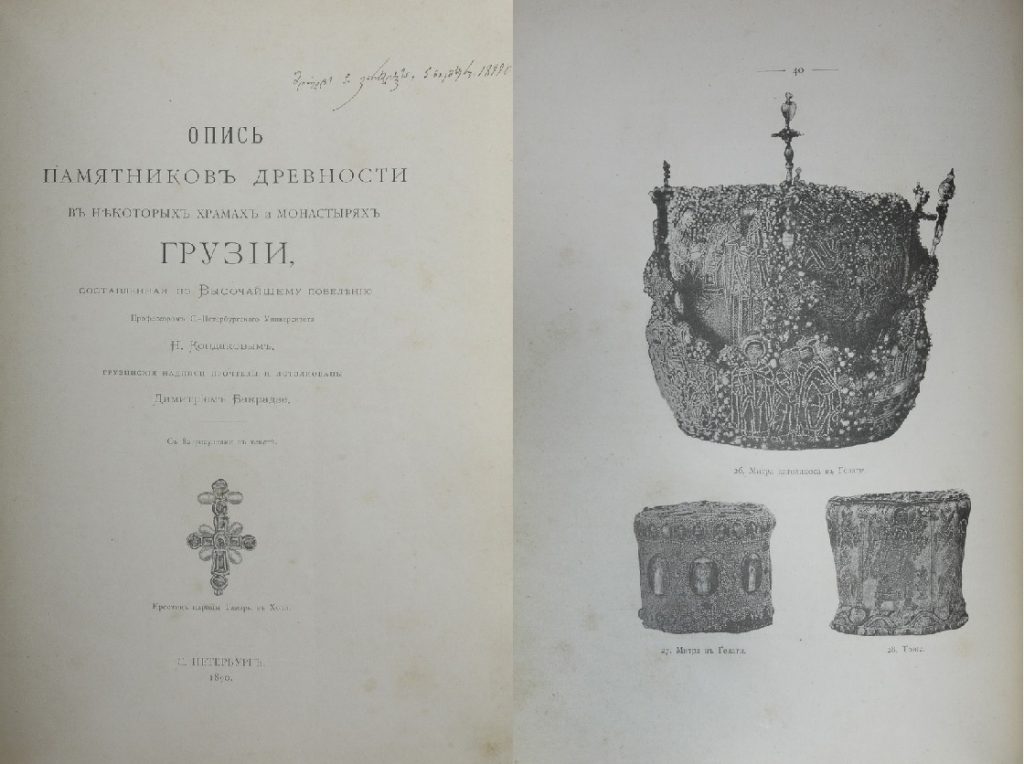

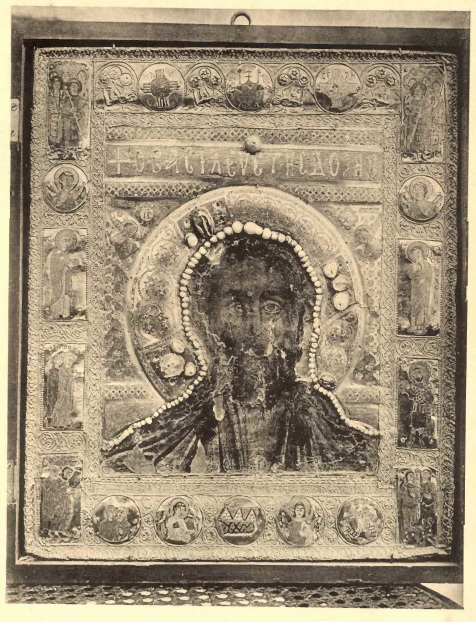

Following this expedition, Kondakov’s subsequent fieldtrips usually ended with a major research report. In this way, he introduced a great number of unknown monuments to wider scholarship. A trip to Georgia in 1889, for example, unearthed rich material for the history of Byzantine and Georgian applied arts and architecture. Yet again, this expedition was not launched on academic grounds. The reason for its undertaking was widely known to the nineteenth-century academic public,[2] namely it was due to the discovery of extraordinary large-scale thefts from the medieval monasteries of the Caucasus. Stepan Sabin-Gus,[3] an enterprising photographer with local connections, had received permission from the Georgian church authorities to replace damaged and worn-out icons and utensils with new, modern works. His indiscriminate selling-off of valuable artefacts meant that many of the most precious medieval enamels that used to adorn the icons in Georgia subsequently appeared in private collections.

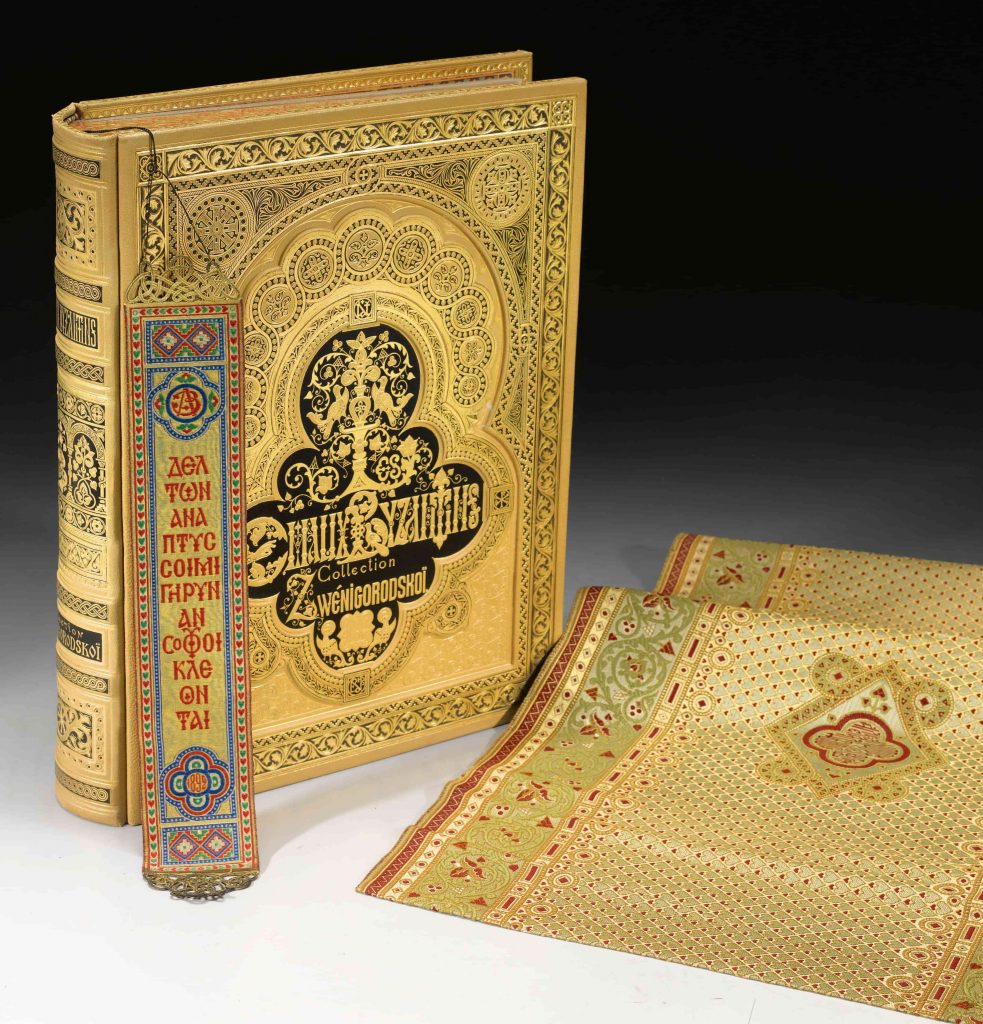

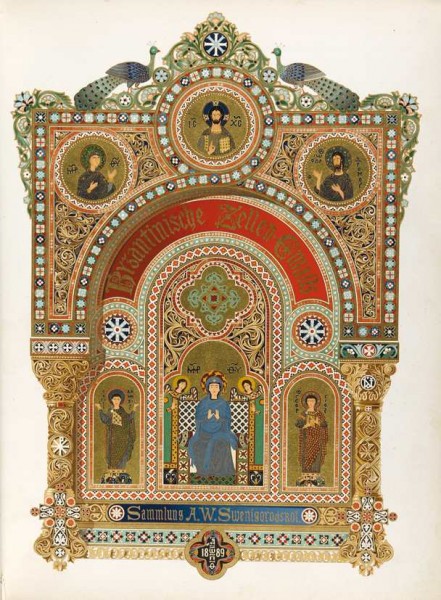

The richest among these was the collection belonging to Alexander Viktorovich Zvenigorodsky (1837-1903), the Petersburg magnate and philanthropist. Before his trip to Georgia, Kondakov had already become acquainted with this extraordinary corpus of enamels and had even produced a book on the subject. Zvenigorodsky, wishing to publish his own collection of Byzantine objects, offered the project to Kondakov, who was then Senior Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Art at the Hermitage Museum. The scholar agreed, but set his own terms of collaboration. As noted in a letter from Zvenigorodsky to Kondakov[4], the Byzantinist didn’t want to become an antiquarian for a private collection gathered by a nouveau riche patron, but instead proposed to devote the volume to the history and technology of cloisonné enamel in general. Within this, Zvenigorodsky’s collection would be included as additional material.

Thanks to the collector’s extravagant demands, the published volume (1892) became one of the most expensive books in Russian history, known as the “Russian miracle” of design and printing. Zvenigorodsky hired artists to produce engravings and chromolithographs from the objects themselves, while the decorative details and binding were created using gold and brocade. The Russian version was typed in a font specially cast for this edition, based on letters from the eleventh-century Ostromir’s Gospels, the earliest dated manuscript of Kievan Rus. According to Vladimir Vasil’evich Stasov, who wrote a history of the book’s production,[5] it was never designed for sale. Almost all of the 600 copies (200 in Russian, 200 in French and 200 in German) were donated to libraries, museums and other research institutions around Europe, with only a few going to individuals. Having publicised his collection in such spectacular fashion, Zvenigorodsky then tried to sell it. In 1894, he approached the Imperial Archaeological Commission and proposed that it acquire the enamels for the Hermitage, but the Russian State unfortunately had more urgent expenditures. Eventually, the collection was bought by John Pierpont Morgan I (1837 – 1913) and passed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1913-1917.

The Georgian matter that really interested the Russian state was the prevention of future thefts, by recording the antiquities still held by the distant Caucasian monasteries. By the personal order of Tsar Alexander III, Kondakov was sent to the Caucasus to catalogue the objects preserved in the sacristies of the main Georgian foundations. The Tsar appointed Dmitry Zacharovich Bakradze (1826-1890), a Georgian historian and corresponding Member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, as the second member of the expedition. The Georgian scholar was responsible for reading and translating inscriptions on icons, revetments, enamels and liturgical objects, as well as for studying the general content of the ancient manuscripts described in the report. The expedition examined the sacristies of the monasteries in Gelati, Motsameti, Nikortsminda, Hopi and Martvili, together with a number of churches, including the sacristy of Zion Cathedral in Tbilisi. Kondakov’s report appeared in 1890, accompanied by multiple photographs and translations of ancient Georgian inscriptions. As Ivan Foletti has noted, a significant further purpose of this text was to represent the medieval region as a cultural periphery, both of the original Byzantine state and of the present Russian Empire.[6] In this way, the report ignored Georgia’s period of independent statehood and deprived it of its cultural diversity.

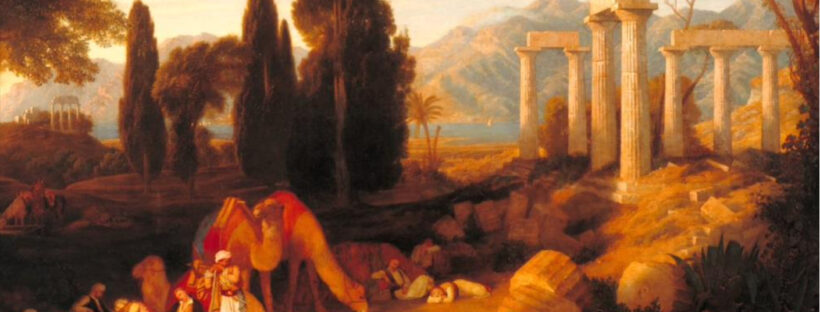

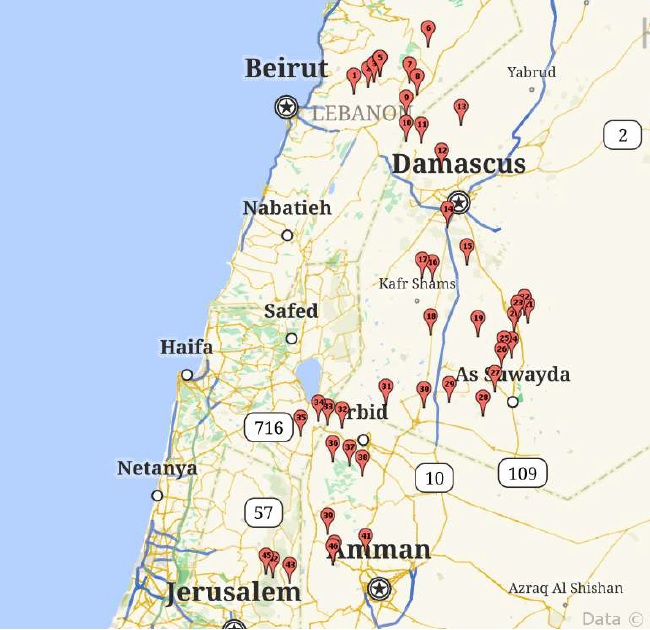

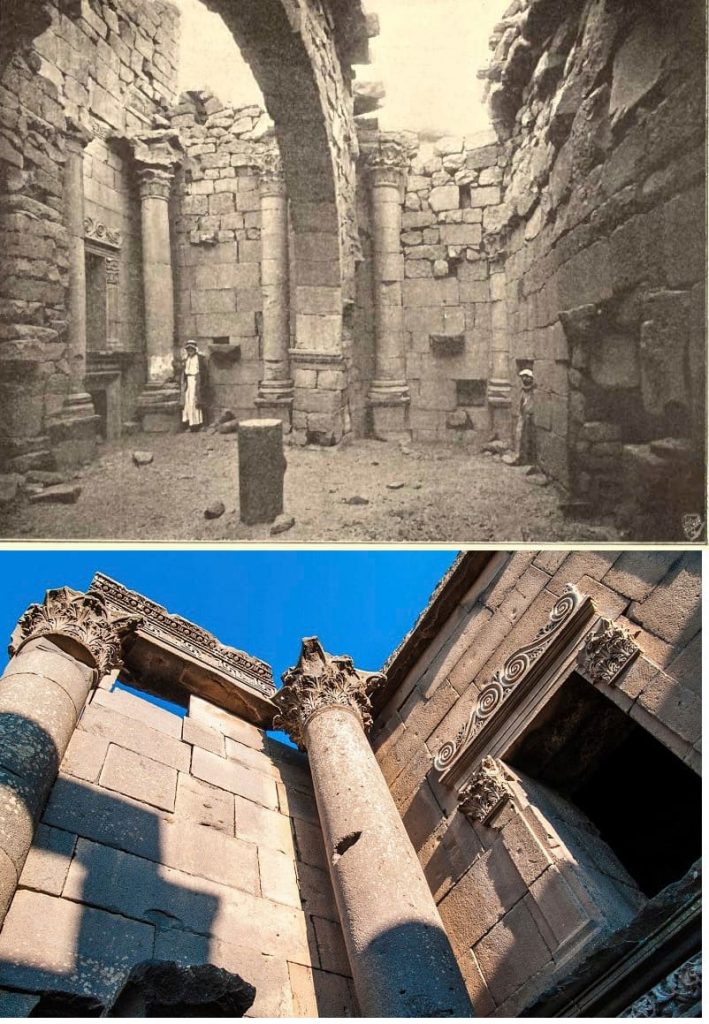

In 1891, Kondakov headed an expedition on behalf of the Imperial Orthodox Palestinian Society to study antiquities in Syria and Palestine. Among his companions were historians Yakov Ivanovich Smirnov and Akim Alexeevich Olesnitsky, a photographer from the Imperial Archaeological Commission called Ivan Fedorovich Barshchevsky, and two artists, Alexei Danilovich Kivshenko and Nikolai Andreevich Okolovich. This expedition received an unprecedented level of support from the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society which provided 20.261 rubles in funding, twice the amount of the annual budget of the Russian Archeological Institute in Constantinople. The number of expedition participants was also unprecedented: twenty-seven people, accompanied by an impressive caravan of forty pack animals and local guides. But the reason for this generosity lay in the political interests of the Russian State.

The expedition travelled to Beirut by sea. The team followed the main roads used by merchants and hajiis and stayed overnight in small towns and villages. The route envisioned by Kondakov, however, could not be completed due to the cholera epidemic affecting southern Syria, northern Palestine and some towns in Transjordania. Where towns were closed for quarantine, the travelers were forced to stay in tents, experiencing many difficulties in the arid and rocky territory between Amman and Jericho

The Imperial Orthodox Palestinian Society was a religious and educational NGO whose aim was to establish and spread the influence of the Russian Empire in the Middle East. It included, besides missionaries and archeologists, a number of Russian agents who made connections with local religious and secular administrations, primarily targeting Arabs dissatisfied with Ottoman bureaucracy. In addition, the Society was a source of official and unofficial information for the Russian diplomatic services.

Kondakov’s expedition was part of the immediate Russian political agenda. Alongside his archeological and art historical mission, the scholar received special secret instructions issued directly by the Imperial family (Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich).[7] These instructions requested him to conduct secret research excavations in Jericho, “without unnecessary noise and rumors”,[8] as the Russian government did not intend to apply for an official excavation permit from the Ottoman administration. The main purpose of the excavations was to locate ancient church ruins on which the Russians could potentially ‘reconstruct’ an Orthodox church. As the Ottoman administration didn’t allow the erection of new Christian sanctuaries, this was the only way to establish a representative office of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Holy Land. Kondakov’s search was successful: in the center of Jericho, Smirnov’s sub-group found the remains of a Byzantine basilica,[9] which provided the justification the Russians needed to reconstruct a church and establish the Russian Church branch office still in existence today.

Another important assignment was to “visit local Orthodox villages along the way,”[10] especially in the Transjordan region, nowadays the state of Jordan. Kondakov planned a route which started in Beirut, passed right through Syria and Transjordania, crossed the River Jordan near Jericho and ended in Jerusalem. This convoluted itinerary allowed the collection of new demographic and economic data about this rarely visited part of the Middle East, in particular about its Christian population. According to the secret attachment to the expedition plan,[11] Kondakov was “to obtain the most accurate answers” to questions concerning the number of village residents, churches, schools, teachers, priests and the sources of their income. This collection of data on the Orthodox population in the Holy Land was not only a matter of general state interest, but also a subject of critical importance for the development of Russia’s foreign policy. By the 1890s, the Russians saw two possible ways to establish their political and religious presence in Palestine: they either could issue a loan, as requested by the local Greek clergy, or sponsor village schools and churches directly, thus bypassing the Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Both had their drawbacks: the sum of the loan was burdensome, while direct interference could endanger the existing tolerant relations with the Orthodox Church in Palestine.

Kondakov largely fulfilled the secret demands of the State (stating in his report that the Greeks requested money in order to steal it, rather than invest in churches and schooling). He also produced a book which reported his Archaeological Journey through Syria and Palestine (1904). Here, he meticulously described not only the ancient and medieval monuments of Lebanon, the Hawran region, Transjordan, Palestine, and Jerusalem, but also shared his vision of Christian archeology and offered observations on the anthropological landscape of the region. In the introductory chapter, he actively rejected the confessional approach to Palestinian archeology, considering it too narrow and exclusive. He viewed the archeology of the Holy Land as methodologically no different from that of any other region, as it “must be developed in accordance with the general methods of art historical studies, if it wishes to seek positive knowledge…”.[12] Criticizing traditional Biblical archeology, he also expressed his dissatisfaction with purely formal analysis of Palestinian art (referring to the Viennese art historian Alois Riegl), whose approach, he felt, excluded the historical circumstances surrounding the origin of a monument.[13]

Russian officials, however, were not inclined to offer significant funding when a fieldtrip could not lead to tangible political results. In 1895, Léon Gustave Schlumberger and Gabriel Millet, both members of the French Academy, proposed to the Russian Academy of Sciences the organization of a joint expedition to Mt. Athos. This endeavor should have resulted in a multi-volume publication of the artistic, diplomatic, historical, and literary monuments belonging to the monastic community, but the Russian Academy considered the project too expensive. Instead, Kondakov and several of his colleagues were ordered to organize an abridged expedition on their own. Kondakov published the results of the trip in his report The Monuments of Christian Art on Mount Athos (1902). This brief overview of eighteen monasteries and one skete, primarily addressed the icons, precious objects and manuscripts preserved in the sacristies of the ancient foundations.

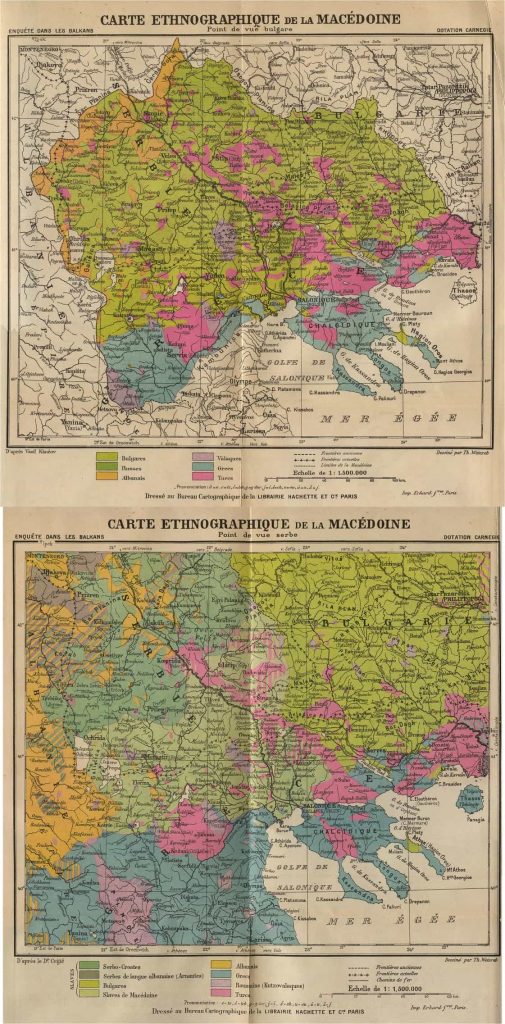

After the Berlin Congress following the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War, international diplomacy and scholarship faced the so-called ‘Macedonian question’. The ethnically, linguistically and religiously diverse population of the region gave grounds for all emerging Balkans nations (Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia) to claim this territory as a hereditary part of their nation, but the region’s diversity also prevented the international community from finding a decisive solution to the problem. Traditionally, politicians and diplomats of the Russian Empire had supported the Bulgarian State which re-emerged largely due to the Russian victory over the Turks in 1878.

Despite the international importance of the Macedonian issue, the Russian government had only a vague idea about the state of affairs in this region. In 1900, therefore, the Imperial Academy of Sciences sent an expedition to analyze the ethnic situation on the ground and to determine whether there was historical, linguistic, or religious evidence to support the claims of the conflicting parties. As with the expedition to the Holy Land, the Romanov family personally regulated the composition and agenda of the research group, with Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich directly appointing Kondakov as the group leader.

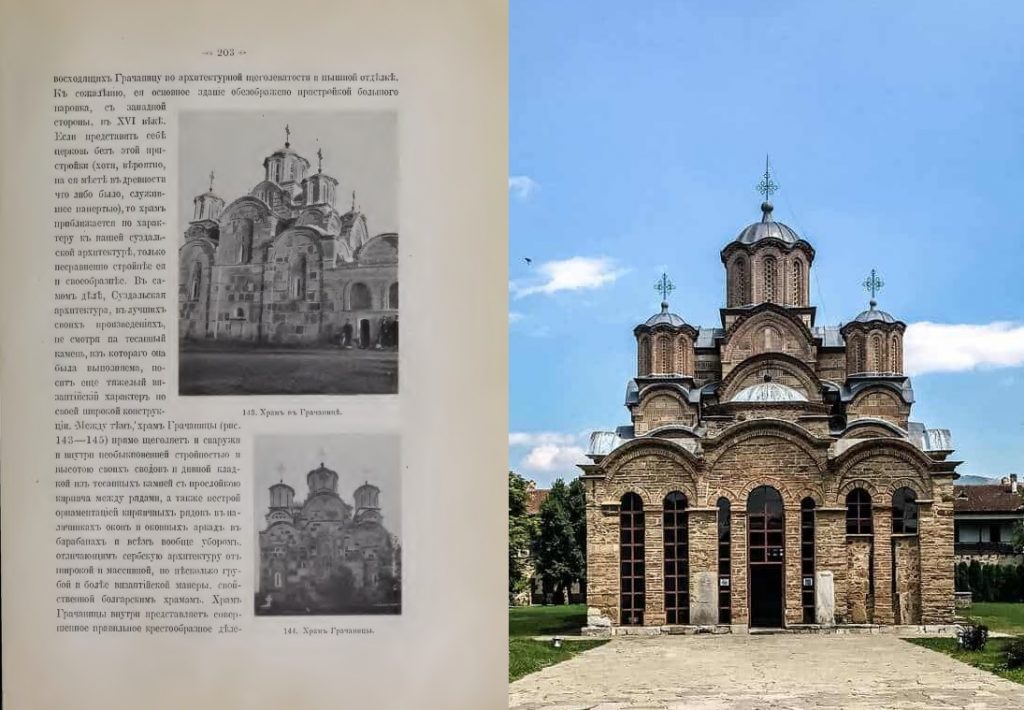

Kondakov’s choice was likely motivated by his previous success in Palestine, as well as by his expertise in art history. According to an earlier expedition report by Pavel Nikolaevich Milyukov, Bulgarian church authorities had destroyed or covered up portraits and inscriptions related to Serbian historical figures in order to erase any evidence of Serbian presence in the region.[14] Kondakov’s role, therefore, was to evaluate the condition of the historical monuments, compose a non-biased report on the scale of contemporary alterations and damage, and discuss the significance of the medieval images and inscriptions in light of current ethnic and political problems.

In his research group, Kondakov included Milyukov, as well as the philologist Petr Alexeevich Lavrov, the architectural historian Petr Petrovich Pokryshkin, and the photographer Dmitry Konstantinovich Krainev. These academics clearly recognized the political aims of the fieldtrip. As Kondakov wrote in his report, “the goal was to strive to establish such scholarly historical, archaeological and philological foundations that could be used in the future when raising a major political issue, formed both by the current position of Macedonia in the Ottoman Empire, … and by its ethnic composition in relation to the neighboring countries and nationalities of the Balkan Peninsula”.[15]

It is usually believed that the Russian art historian supported Bulgarian claims to the territory, however his views were actually more nuanced, as demonstrated in the political commentaries that he included in his Macedonian report alongside high-quality historical, iconographic and stylistic analysis of the monuments. First, he pointed to the Albanians as the source of “the constant turmoil and lack of civil order, and hence the fear that oppresses the country”. He represented them as “a wild tribe of mountaineers-shepherds… inclined to predation,”[16] and said they were used by the external powers to destabilize the Balkan Slavic states, with European and Turkish diplomacy forcing the Albanians to create unnatural political unions and to revolt. Kondakov was, however, equally unimpressed by the Balkan Slavic nations, commenting that “in Slavic countries… treacherous instincts are not only teeming in abundance everywhere, but are often the exclusive way of conducting politics.”[17] Thus, in the concluding pages of his report, Kondakov proposed his own vision of the future Balkan Peninsula. Taking into consideration the growing Albanian menace, as well as the militant, deceitful inclinations of the neighboring Austrian and Turkish Empires, one should see Slavic Serbia and Bulgaria not as competitors for territory, but rather as parts of a new political Slavic Union.[18] This vision of the Balkan future subscribed to the unfulfilled dream of Pan-Slavism ideology.

Looking at these constant struggles in Kondakov’s reports to find a balance between academic and political subject matter, one may suggest that the research expeditions, or rather their financing, was always dependent on the agenda of the Russian imperial government. From the viewpoint of the imperial establishment, an art historian was a perfect spy… in the nineteenth century as much as during the Cold War. However, a historian might have a choice: to reject politically-motivated funding and conduct an expedition at personal expense. And Kondakov did travel much on his own, but the materials he collected during these trips were never shaped in the form of ordered reports.

When, in 1916, the Russian academic milieu celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the research activities of Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov, his student A.M. Belov noted: “Like an ancient Argonaut, N[ikodim] P[avlovich] personally embarked on a number of journeys <… ˃, sparing neither funds, nor strength, nor his body. In Russia, it seems, there is no boondocks preserving old heritage, dear to his heart, which he would not visit to study. The Russian North with its remnants of hoary antiquity, Central Russia with its monuments dating back to the Moscovite Period, Kievan Rus with its mounds that still remember the Scythians, and finally, the Caucasus with its monuments of early Christianity – all these places attracted N[ikodim] P[avlovich] <… ˃. He knows the countries of the Balkan Peninsula very well, Turkey, especially Constantinople; he lived for a long time in Greece and Italy, explored the length and breadth of Western Europe, studying its artistic treasures, and more than once made trips to places where travelers rarely venture. So, with the same aim of bringing important material to the light of the day, N[ikodim] P[avlovich] traveled to the Sinai Peninsula, to the monasteries of Mount Athos, to the islands of the Greek archipelago, and, finally, to Syria and Palestine.”[19]

[1] Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov, Путешествие на Синай в 1881 году. Из путевых впечатлений. Древности Синайского монастыря [The Trip to Sinai in 1881. From Travel Impressions. Antiquities of the Sinai Monastery] (Odessa: Zelensky’s Printing House, 1882): I.

[2] Fedor Ivanovich Pokrovsky, Академик Никодим Павлович Кондаков [Academician Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov] (St. Petersburg, 1911): 4-5.

[3] The name of the photographer does not appear in Russian official sources, but it was known to some Art Historians in Georgia, see: Shalva Yasonovich Amiranashvili, История грузинского искусства [History of Georgian Art] (Moscow, 1963): 257.

[4] Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg branch, fund No. 115, series 2, storage unit 132

[5] Vladimir Vasil’evich Stasov, История книги «Византийские эмали» А.В. Звенигородского [The History of A.V. Zvenigorodsky’s Book Byzantine Enamels] (St. Petersburg, 1898): 4.

[6] Foletti, Ivan. “The Russian view of a ‘peripheral’ region: Nikodim P. Kondakov and the Southern Caucasus,” Convivium 3/Supplementum (2016): 20-35.

[7] Archive of Foreign Policy of the Russian Empire, fond No. 337/2, series 873/1, case no. 597, fols. 7-18. The documents are partially published in: A.S. Smirnov, “Неизвестные страницы археологических путешествий Н. П. Кондакова [Unknown Pages of Archeological Journeys by N.P. Kondakov],” Rossijskij archeologicheskij ezhegodnik 1 (2011): 511-525 (here pp. 514-515).

[8] Smirnov, “Неизвестные страницы..”, 514.

[9] Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov, Археологическое путешествие по Сирии и Палестине [Archaeological Journey to Syria and Palestine] (St. Petersburg, 1904): 137-142.

[10] Smirnov, “Неизвестные страницы..”, 514.

[11] Archive of Foreign Policy of the Russian Empire, fond No. 337/2, series 873/1, case no. 597, fol. 18

[12] Kondakov, Археологическое путешествие по Сирии, 1.

[13] Ibid., 22-25.

[14] Pavel Nikolaevich Milyukov, “Христианские древности западной Македонии” [Christian Antiquities of Western Macedonia], Izvestija Russkogo arheologicheskogo instituta v Konstantinopole 1899/4 (1899): 135.

[15] Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov, Македония – Археологическое путешествие [Macedonia – Archaeological Expedition] (St. Petersburg, 1909): 1.

[16] Ibid., 213.

[17] Ibid., 214.

[18] Ibid., 298.

[19] Alexei Michailovich Belov, “Академик Никодим Павлович Кондаков (К пятидесятилетию его ученой деятельности)” [Academician Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov (To the fiftieth anniversary of his academic activity], Istoricheskiy Vestnik 146 (1916): 457-458.

List of Illustrations:

- Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov (1844-1925). Credits: https://ru.wikipedia.org/

- Chersones, Basilica discovered by Count Uvarov, engraving for Proshloe Tavridy by Yu. Kulakovsky (1906). Credits: http://www.krimoved-library.ru/

- Journal Izvestiya Archeologicheskoi Komissii, issue of 1901

- Vues et antiquités du Sinai par M. le professeur Kondakoff (Odessa, 1881) and Photo of the Library of St. Catherine’s Monastery by Jean Raoult. The extremely limited number of copies of the Album (no more than 15 were printed) meant it was already a bibliographic rarity in the 19th century. The Imperial Public Library (today The National Library of Russia in Saint Petersburg) purchased the album on September 3, 1883. This copy, containing 102 passe-partouts with 107 photograph,s is kept in the Polygraphy Department (code RNB. 15.31.1.86).

- Book cover: Histoire et monuments des émaux byzantins par N.P. Kondakov (Francfort sur Mein, 1892). Credits: Credits: https://www.sothebys.com/

- Front page of Histoire et monuments des émaux byzantins par N.P. Kondakov (Francfort sur Mein, 1892) – https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:47267939$1i

- Byzantine enamel with Saint George (The Metropolitan Museum, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/464547), gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, from Zvenigorodsky’s Collection and pl. 9 from Histoire et monuments des émaux byzantins

- Book cover and Katholikos mitre from Gelati Monastery: Opis’ pamjatnikov drevnosti v nekotoryh’ hramah i monastyrjah Gruzii sostavlennaja po vysochajshemu poveleniju professorom S.-Peterburgskogo universiteta N. Kondakovym. Gruzinskie nadpisi prochteny i istolkovany Dimitriem Bakradze (Saint-Petersburg, 1890)

- Travel route from Beirut to Jerusalem of Kondakov’s expedition to Syria and Palestine in 1891

- Sanamayn Temple (Syria), illustration from Arheologicheskoe puteshestvie po Sirii i Palestine (Saint-Petersburg, 1904) and contemporary view

- The Dome of the Rock (Jerusalem), illustration from Arheologicheskoe puteshestvie po Sirii i Palestine (Saint-Petersburg, 1904) and contemporary view (Credits: https://www.flickr.com/photos/palestine_view)

- Georgian icon with medieval revetment of gold and enamel, gift of Mengrelian prince Dadiani Katsia (1770), Sacristy of the Holy Sepulchre Church, illustration from Arheologicheskoe puteshestvie po Sirii i Palestine (Saint-Petersburg, 1904)

- Kondakov and members of his expedition to Mt. Athos with the brotherhood of Vatopedi Monastery (Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg Office)

- Ethnographic map of Macedonia from the Bulgarian viewpoint (above) and Serbian (below). Maps by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (1914). Credits: commons.wikimedia.org

- Gračanica Monastery (Serbia), a page from Makedonija: Arheologicheskoe puteshestvie (Saint-Petersburg, 1909) and contemporary view

—

Bibliography

- Primarily Sources

Belov, Alexei Michailovich. “Академик Никодим Павлович Кондаков (К пятидесятилетию его ученой деятельности)” [Academician Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov (On the fiftieth anniversary of his academic activity)], Istoricheskiy Vestnik 146 (1916): 454-462.

Kondakov, Nikodim Pavlovich. Путешествие на Синай в 1881 году. Из путевых впечатлений. Древности Синайского монастыря [The Trip to Sinai in 1881. From Travel Impressions. Antiquities of the Sinai Monastery] (Odessa: Zelensky’s Printing House, 1882).

Kondakov, Nikodim Pavlovich. Опись памятников древности в некоторых храмах и монастырях Грузии составленная по Высочайшему повелению профессором С.-Петербургского университета Н. Кондаковым. Грузинские надписи прочтены и истолкованы Дмитрием Бакрадзеe [Inventory of ancient monuments in some churches and monasteries of Georgia, composed by the Highest Authority’s command by Professor N. Kondakov of St. Petersburg University. Georgian inscriptions read and interpreted by Dmitry Bakradzee] (St. Petersburg, 1890).

Kondakov, Nikodim Pavlovich. Византийские эмали. Собрание А.В. Звенигородского. История и памятники византийской эмали [Byzantine Enamels. Collection of A.V. Zvenigorodsky. History and Monuments of Byzantine Enamel Technique] (St. Petersburg- Frankfurt am Main, 1892).

Kondakov, Nikodim Pavlovich. Памятники христианского искусства на Афоне [The Monuments of Christian Art on Mount Athos] (St. Petersburg, 1902)

Kondakov, Nikodim Pavlovich. Археологическое путешествие по Сирии и Палестине [Archaeological Journey to Syria and Palestine] (St. Petersburg, 1904).

Kondakov, Nikodim Pavlovich. Македония – Археологическое путешествие [Macedonia – Archaeological Expedition] (St. Petersburg, 1909).

Milyukov, Pavel Nikolaevich. “Христианские древности западной Македонии” [Christian Antiquities of Western Macedonia], Izvestija Russkogo arheologicheskogo instituta v Konstantinopole 1899/4 (1899): 21-152.

Pokrovsky, Fedor Ivanovich. Академик Никодим Павлович Кондаков [Academician Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov] (St. Petersburg, 1911).

Smirnov, A.S. “Неизвестные страницы археологических путешествий Н. П. Кондакова [Unknown Pages of Archeological Journeys by N.P. Kondakov],” Rossijskij archeologicheskij ezhegodnik 1 (2011): 511-525

Stasov, Vladimir Vasil’evich. История книги «Византийские эмали» А.В. Звенигородского [The History of A.V. Zvenigorodsky’s Book Byzantine Enamels] (St. Petersburg, 1898).

- Secondary Literature

Foletti, Ivan. “The Russian view of a ‘peripheral’ region: Nikodim P. Kondakov and the Southern Caucasus,” Convivium 3/Supplementum (2016): 20-35.

Foletti, Ivan. From Byzantium to Holy Russia: Nikodim Kondakov (1844–1925) and the Invention of the Icon (Rome, 2017).

Gerd, Lora. “Russian Imperial Policy in the Orthodox East and its Relation to Byzantine Studies,” in: Imagining Byzantium. Perceptions, Patterns, Problems, eds. A. Alshanskaya et al. (Mainz, 2018): 93-100.

Khroushkova, Liudmila “Kondakov,” in: Personenlexikon zur Christlichen Archäologie. Forscher und Persönlichkeiten, eds. S. Heid, M. Dennert, Vol. 1 (Rugensburg, 2012): 751-754.

Kyzlasova, Irina. “Исследовательские методы. Ф. И. Буслаева и Н. П. Кондакова,” Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta 1978/4 (1978): 87–95.

Kyzlasova, Irina. История изучения византийского и древнерусского искусства в России [The History of Studies of Byzantine and Old Russian Art in Russia] (Moscow, 1985).

Kyzlasova, Irina, ed. Мир Кондакова. Публикации. Статьи. Каталог выставки [Kondakov’s World. Publications, Articles. Exhibition Catalogue] (Moscow, 2004).

Vzdornov, Gerold I. The History of the Discovery and Study of Russian Medieval Painting (Leiden, 2017).

Art Historiographies in Central and Eastern Europe

Art Historiographies in Central and Eastern Europe